Psychedelic therapy & the Metaphysical Menu

Would you like a side-order of Spinoza with that?

You go to a psychedelic therapy clinic for depression. You have a powerful experience which fundamentally alters your view of reality. This in turn alters your sense of self and liberates you from the claustrophobic and anxious ego. You want to make sense of your new worldview, to see if it’s believable in the cold light of day.

Some time after the trip, your therapist offers you a Metaphysical Menu, listing some of the philosophical options available to you to frame your trip.

‘Are you ready to order?’ they smile.

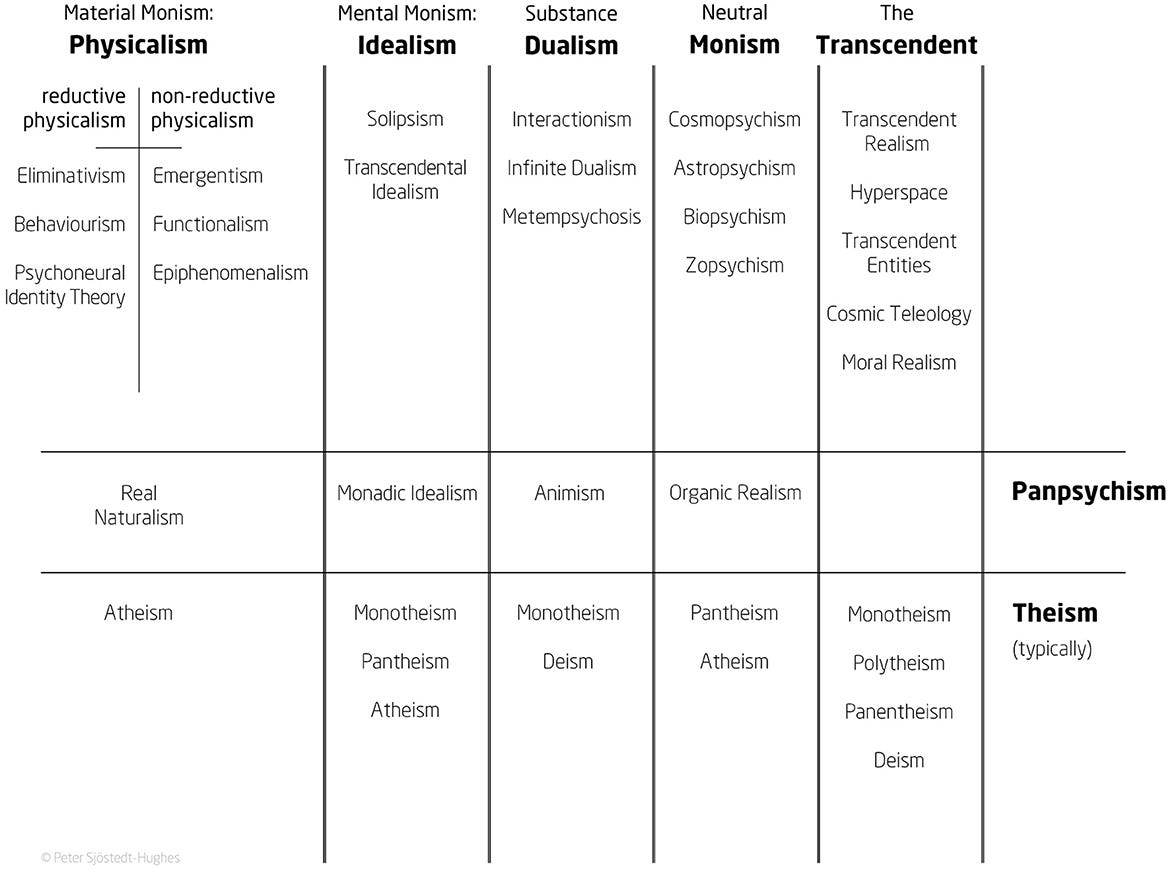

Dr Peter Sjostedt-Hughes is a psychedelic philosopher at the University of Exeter. In a 2022 paper - that has recently attracted discussion and criticism from bioethicists from NYU and Johns Hopkins University - Dr. Sjöstedt-Hughes suggests that some psychedelic experiences could be enhanced by optional instruction in metaphysics, specifically, through the use of a ‘Metaphysical Matrix’, like the one below.

Patients may request the Matrix during the broader therapeutic process and review its contents: descriptions of the worldviews, and the option of discussing them in more depth with therapists better-trained in metaphysical dialogue. In and among a client’s descriptions of their strange experiences, the practitioner could detect overtones of recognised metaphysical systems - and explore cooperatively some form of coherence.

The aim is twofold for Sjöstedt-Hughes. First, to get more philosophy in psychedelia, notwithstanding the specific quality of the Matrix proposal. Experiences rich in philosophical and metaphysical content bring their own specific needs, which transpersonal and standard approaches may struggle to capture. Sjöstedt-Hughes coined the notion of metaphysical experiences, which result in intellectually-expressible changes to one’s beliefs. This is different to standard mysticism, he says, which ends in a felt and experiential sense of mystery.

Second, we know that psychedelics can change people’s worldviews, and in ways that can variously create clinical benefits or harms. 80% of respondents in a Johns Hopkins survey of DMT users confessed that their trips had shifted their fundamental conception of reality. Two studies from groups at Imperial College, London and Johns Hopkins University have documented general, albeit moderate, shifts in the direction of mind-centred metaphysical ideas like panpsychism and idealism, including from surveys and clinical data. These suggest variously that the mind is part of the universe’s essential structure. Timmerman et al (2021) found that ‘changing your mind’ away from physicalism - the metaphysical belief that all things are ultimately reducible to physics - correlated with “increases in psychological wellbeing”. Those administered psilocybin in an Imperial trial for treatment-resistant depression exhibited the pattern; it did not occur among those administered an SSRI.

The Matrix could help to tip the balance towards benefit, Sjöstedt-Hughes argues, by reassuring patients that possibly exotic new worldviews have philosophical heritage and they aren’t just going crazy. He tells me:

[I]nstead of simply dismissing the experience they had maybe a few weeks or a few months later as obviously delusional or whatever - you know, you thought ‘’God was nature’, that it felt good at the time, but obviously, it's complete rubbish”, Sjöstedt-Hughes told me, “you might think to yourself, instead of, in other words, falling down to the ideology of one's culture, one gets the options of actually giving it a little bit more credence, or at least when one can realise… that there’s a lot of good reasons for many metaphysical views like pantheism, or, that God is nature.

Meta-what-now?

Why care about metaphysics? Because nothing is metaphysically neutral: every system and approach carries its own set of ultimate assumptions about what reality is and how it works. Without some guidance in metaphysics, Sjöstedt-Hughes worries that patients may “default to the [metaphysical] ideology of their culture”, in ways that might compromise their epistemic autonomy and authentic beliefs. Psychedelic science, for instance, tends towards a neurological flavour of physicalism or materialism, which holds that matter is the cosmos’ fundamental constituent. Such metaphysics are seen in claims that the brain is a computer, which may be ‘freed up’ through modulating certain ‘priors’ (a term from statistics), or that ‘the ego’ is the ‘Default Mode Network’, an area of the brain that can be ‘switched off’ by flicking a certain ‘switch’. That such ideas are shared by big names in the field, like Robin Carhart-Harris and David Nutt, lends them an air of seemingly ‘neutral’ authority - despite being questioned even on scientific terms by others like Dr. Manoj Doss.

If physicalism is the default metaphysics of western culture, the default metaphysics of psychedelic culture tends towards the New Age and transpersonal. If applied well, Sjöstedt-Hughes suggests, the Metaphysics Matrix can therefore help people retain an epistemic or philosophical flexibility without being sucked into the dominant materialism of the academy, or the dominant New Age pot pourri of psychedelia.

I’ll take the Spinoza with a side-order of Kant

Psychedelic therapists and psychologists have recently come out in criticism of Sjöstedt-Hughes’ proposal. In a recent Special Commentary by Johns Hopkins University’s Professor David Yaden and NYU’s Katherine Cheung, the authors claimed that the Menu “may run the risk of imposing certain worldviews, or may inadvertently pressure them to place their experience within a metaphysical framework.”

More after the paywall. Paid subscribers support our research and also get access to our article and video archive, including our discussion with Bill Brennan and Alex Belser on the place of spiritual and existential questions in psychedelic therapy.