What's missing from the NYT's Amy Griffin story

The role of the psychedelic guide, and the risk of therapeutic abuse in the underground

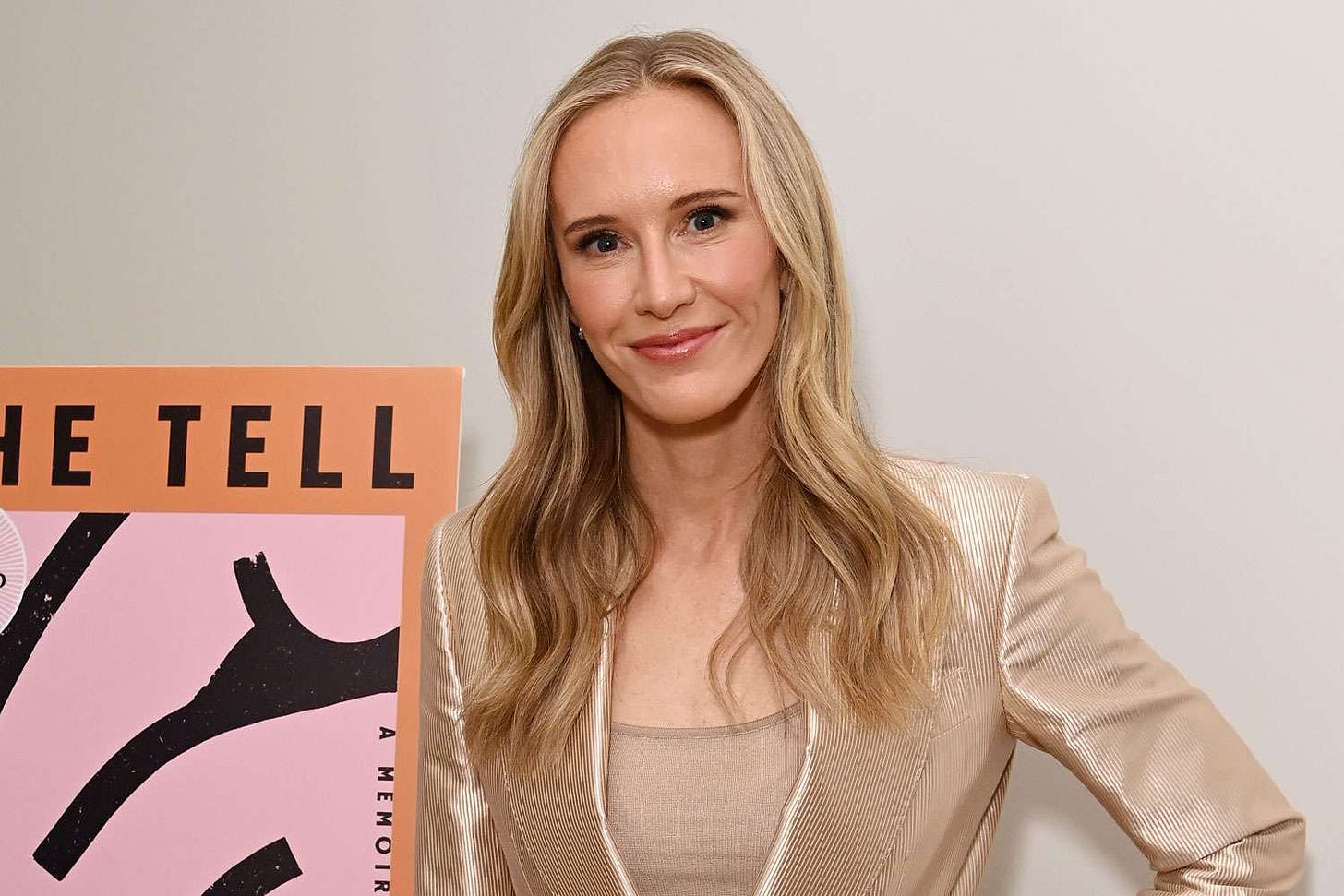

Two weeks ago, the New York Times published a long feature about Amy Griffin’s best-selling book, The Tell. Griffin is a very successful investor, married to a billionaire hedge-fund manager called John Griffin. The two tried underground MDMA therapy with a guide - ‘Olivia’ - and donated $1 million to MAPS and became investors in Resilient, MAPS’ MDMA corporate spin-off. During her first MDMA experience, Amy experienced a memory of being sexually assaulted by a teacher at her school, and over subsequent sessions she recalled further details, of multiple assaults by the same teacher when she was 12-16, and an assault by another man. Her book tells the story of her piecing together the shards of her memory, telling her family, and trying to bring the (now retired) teacher to justice in Texas. She isn’t able to bring a case against him, because of Texas’ statute of limitations, but she does write a best-selling book, helped by endorsements from figures like Oprah Winfrey, Drew Barrymore, Reese Witherspoon and Gwyneth Paltrow. Meanwhile, in her home-town of Amarillo, Texas, the teacher has apparently been identified and gone into hiding.

The New York Times investigation, written by book-reviewer Elizabeth Egan and society reporter Katherine Rosman, suggests Griffin may have experienced false memory. They point out that no one else has come forward to accuse the teacher, who Griffin accuses of violent repeated rape. They also interview a fellow pupil who knew Griffin at school, who says the details of the book match her own experience being abused by another teacher (Griffin’s lawyer says she’s a fabulist). They question the validity of psychedelic-induced recovered memories. And they point out all the money, power and influence Griffin has to promote her book and damage the life of the teacher without him having an opportunity to defend himself.

The Times investigation has prompted a wider media discussion about Griffin’s story and psychedelic-induced recovered memories. The Times UK interviewed false memory expert Elizabeth Loftus, an old foe of Bessel Van Der Kolk’s from the memory wars of the 1990s, while the New York Post declared: ‘As more layers are peeled back, this starts to feel less like a memoir and more like a reckless celebrity infomercial for psychedelics.’

We do not know if Griffin’s recovered memories are true or not. But the New York Times story (written by two journalists who have not written about psychedelics before) misses out one crucial component of this situation: the role of the psychedelic ‘facilitator’.

What does a psychedelic facilitator do?

A psychedelic ‘facilitator’ or ‘guide’ can be anything from a basic trip-sitter who makes sure a person is safe while tripping, to a therapist who prepares a person before a trip, guides them through it, and then helps them make sense of the trip afterwards, perhaps working with a client through a months-long multiple-session journey of self-discovery involving the uncovering of a lot of psychological material. The deeper and longer the work, the more it requires expertise, professionalism, ethics and safeguards.

A good professional therapist obeys certain core ethical principles. They respect the autonomy of the client by properly informing them of the treatment and any risks, and not imposing their own opinions or values onto the client. They seek the client’s healing and not their own selfish interests. A licensed therapist has to obey ethical codes around things like power dynamics, transference and the risk of dual or triple relationships leading to therapeutic abuse, which is when a therapist exploits a client for their own goals. They risk their license and their livelihood if they break that ethics code.

According to trial lawyers Jenner Law, who are experts in cases of therapeutic abuse, common warning signs of therapeutic abuse include:

Meeting outside the therapist’s office

Personal contact between you and your therapist outside of therapy sessions

Sexual communication or contact, including inappropriate sexual jokes, suggestions, or questions

Violation of psychological or physical boundaries

Giving or asking for gifts

Encouragement of a dependent relationship

So what sort of care did Amy Griffin receive?

Olivia

In the book, John has been trying MDMA therapy with an underground guide, Olivia, and thinks Amy should meet her. The three have dinner.

Over dinner, Olivia fielded my questions. She had been in the psychedelic movement for decades, and she was gentle and knowledgeable as she explained her work to me. “So how long have you been a therapist?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m not a therapist,” she said. “I’m a facilitator.”

“What exactly does that mean?” I asked. “What are the credentials?”

She laughed. “A lot of experience.”

“Experience with what?”

“Witnessing,” she said, “as people find answers within themselves. I’m just there to facilitate an experience for them.”

“And the experience involves drugs?”

“I call it medicine,” Olivia said. “I always start with MDMA…I’m not there to shape your experience, only to support you throughout. I won’t interfere or prompt you in any way, so you can turn inward and focus on your own wisdom. And after, I’m here to help you integrate what you’ve learned.”

“But if these drugs are so helpful, why aren’t they legal?”

Olivia smiled. “Well, there’s a complicated answer to that question that involves politics, racism, and the American obsession with morality, but long story short: Nixon and Reagan’s war on drugs ended up criminalizing chemicals that had tremendous potential to heal and transform—even though psychiatrists were using MDMA experimentally in sessions in the seventies, long before it became popular on the street.”

This first meeting raises some initial concerns around boundaries and professionalism. They’re meeting in a social situation, for one thing - the beginning of a deep ‘friendship’ between Olivia and Amy, which we’ll discuss shortly. How do the Griffins know Olivia has ‘decades of experience’? They can’t Google her reviews or check out her credentials. In fact, they have little way of knowing what is normal or acceptable in this experimental treatment - the power is very much in Olivia’s hands.

Does Olivia give Amy proper warning of the potential adverse effects of psychedelic therapy? If she does, Griffin doesn’t mention them in her book. Olivia doesn’t apparently say psychedelic experiences can sometimes lead to destabilization lasting months or even years (which is what happens to Amy Griffin). When Amy asks why psychedelics are illegal, Olivia gives a self-serving reply, blaming ‘racism’ rather than people having severe adverse experiences in the 1960s.

Amy has at least three more sessions with Olivia - we don’t know how many sessions she has, or whether she just does MDMA or takes other drugs. Because this is the underground, Amy doesn’t know precisely what she takes. We also don’t know if Olivia genuinely doesn’t shape Amy Griffin’s experiences or ‘prompt’ her in any way. There’s one incident at a later session where Griffin says:

“I don’t know how I’m going to drop back into a normal life of dinner parties and small talk.”

“Oh, Amy,” she said softly. “You might not want to go to those dinner parties anymore.”

That’s prompting and subtly socially isolating the client - drop those friends, trust in me. A professional, ethical therapist is careful not to tell a client what to do, because that risks making the client overly dependent on your advice.

Olivia becomes a ‘trusted friend’ of Amy’s. They text regularly and socialize, like this occasion

on a summer night not unlike the one when she’d first entered my life. MDMA had recently been legalized for therapeutic use in Australia, which indicated that the rest of the western world would likely follow in the years to come. I was wearing a bracelet Olivia had given me for my birthday a year earlier, which had become one of my most cherished possessions - a tangible link to the leap of faith I’d taken. Just like the one I’d held on her wrist during my first session, the bracelet was made of coins that I now knew dated to 1912, the year MDMA was invented.

All of this would flash warning lights for any licensed therapist. Therapists’ professional codes of ethics warn therapists not to socialize with clients, not to give them expensive gifts, not to become work colleagues, lovers or ‘trusted friends’, because this is not a relationship of equals, like a friendship. This is a paid professional service where the therapist is in a position of power, and is obliged to act in the best interests of the client, and not in their own interests. When you blur boundaries and develop dual or multiple relationships, the client may feel confused and pressured to obey the therapist’s demands.

A sense of dependency or even love and worship can build up through therapeutic transference - Amy calls Olivia ‘the Divine Feminine, the light you cast in this world made me feel secure enough to chart this course’. This ‘guru-worship’ again creates the potential for over-dependency, exploitation and abuse.

All these potential ethical risks of the therapeutic relationship - transference, dependency, guru-worship and the risk of manipulation - are amplified by psychedelics, because psychedelics dissolve ego-boundaries and lead to a mystical-type experience which bewilders the client and can make them dependent on the guide and sometimes very reverent towards them, especially if it’s their first trip. So psychedelic therapists should be even more careful about ethical risks.

But Amy’s session happened in the psychedelic therapy underground, in which very different codes of behaviour grew up in the last 40 years of prohibition and were allowed to go unscrutinised, undiscussed and unchallenged. In the freewheeling culture of underground therapy, boundaries between guide and client were / are often dissolved and harms are rarely reported. That led to situations like Francoise Bourzat and Aharon Grossbard, a husband-and-wife team who were prominent guides in the US underground with some high-net-worth clients. They were accused of running a cult-like network in which some clients ended up feeling manipulated and emotionally harmed by the guru-like guides.

The risk of financial exploitation is increased in this case because Amy Griffin is a billionaire, connected to many other wealthy figures. Olivia gives Amy a bracelet, which becomes one of her ‘most treasured’ possessions, because it anchors her to her first MDMA experience with Olivia.

‘This medicine is going to help so many people’, I said.

‘It already has’, Olivia said. ‘We just haven’t been able to talk about it.

I thought back to how much work I’d done in the immediate aftermath of my sessions, and how much I’d struggled with anxiety, flashbacks, and depression. I remembered how much I’d relied on John, my family and Lauren at the time. Without them, I didn’t know where I’d be.

‘People are going to need resources’, I said. ‘So if they open up the way I did, they have the space and support to sort through it slowly and integrate what happened’.

Did Amy ever give Olivia expensive gifts or donations, beyond the cost of the sessions themselves (which is likely to be in the thousands of dollars)? That would be inappropriate in a therapeutic relationship, even more so if it occurred after a psychedelic session when the client’s suggestibility is enhanced. We emailed Amy Griffin to ask her, but didn’t hear back.

MAPS and underground guides

We don’t know if Amy and John Griffin gave gifts or donations to Olivia. We do know they gave $1 million to MAPS, Rick Doblin’s psychedelic non-profit, and then became shareholders in Resilient, MAPS’ corporate spin-off. We asked MAPS about this - Rick Doblin, founder of MAPS, says Amy and John became donors to MAPS before either tried MDMA therapy.

The Griffins are not the only high-net-worth MAPS donors to be connected to underground guides by MAPS. Elizabeth Koch, heiress to the Koch fortune, attended a MAPS psychedelic conference, and then did psychedelic sessions with an underground guide, and subsequently gave $2.7 million to MAPS and later became an investor in Resilient. Doblin tells us: ‘I did introduce Elizabeth to the underground therapist she worked with, and I was sure of the professionalism of that therapist.’

A 2024 Business Insider investigation into MAPS raised this issue of connecting donors to underground guides and then subsequently seeking donations:

One employee said MAPS had always had a “strategy to fundraise around the drug experience,” including inviting prospective donors to drug-fueled parties. Doblin would come to meetings and tell stories about courting donors by giving their family members MDMA therapy, another former staffer recalled, adding, “I guess seeing is believing with some of these substances.” Providing donors with drugs was “not common,” Doblin told BI over the phone in March. But, he said, “everyone deserves healing.” (MAPS’s director of communications, Betty Aldworth [now co-executive director], told BI that drug-fueled parties did not “represent MAPS’s fundraising strategy.”)

Doblin told me in 2024: ‘I know to wait to speak to people about donations well after any non-ordinary state of consciousness. Furthermore, I have never heard in any way, or been told by donors that they felt being taken advantage of by being asked to make a donation at any time.’ He adds: ‘Drug-fueled parties intentionally gives the wrong impression since these were not ‘parties’ but contexts for inner exploration. This language is intended to be inflammatory and harmful and is incorrect.’

To be clear, the psychedelic renaissance would not have happened without Rick Doblin. And maybe it wouldn’t have happened without high-net-worth clients funding MAPS and other psychedelic causes. And maybe they wouldn’t have provided hundreds of millions in funding unless they themselves felt helped by underground psychedelic therapy. But to anyone outside psychedelic culture, this will seem a weird and ethically-fraught way to fund drug development.

Introducing someone to an unlicensed underground guide raises ethical and psychological risks. Underground guides usually have no licensing board for clients to complain to, no ethics code they have to obey. Even if they’re a licensed therapist, it’s difficult for clients to sue them, because lawyers aren’t yet familiar with psychedelics, while licensing boards are overstretched and take years to investigate ethical complaints.

Is Doblin always sure of the professionalism of the guides he connects people to? Rick told us:

The issue of how to evaluate underground therapists is a genuine concern. However, I think your summary of the risks doesn’t take into account that some underground therapists are highly skilled, compassionate and ethical. They are profoundly aware of the risks to themselves from engaging in treating people with medicines that are currently illegal. Also, some underground therapists are licensed to provide therapy or are psychiatrists, risking their licenses to help people suffering now who have often been through all sorts of medications and other therapies that didn’t provide sufficient relief.

Regarding risks to underground therapists, the biggest risk is not when the therapy doesn’t help or hurts the patient and the patient complains to authorities. The biggest risk is when the therapy goes well and the patient makes some changes in their lives like leaving a relationship or a religious community. Those left behind may then complain to the authorities.

There’s also the issue of the unethical nature of the drug war that has made these substances illegal.

Doblin identifies risks to the therapists, not to the clients. There are of course underground guides who try to work ethically and who do their best not to harm their clients (some of them read this newsletter). MDMA therapy shows very promising results and many people say they have been helped a lot by it. But there are also risks. In the underground, there’s no agreed ethical code, or framework of checks and supervision against bad behaviour, and there are some predatory people taking advantage of that. As one veteran of the psychedelic industry put it to us: ‘The illegality of psychedelics enabled some weird people to work in the underground who should never have been anywhere near mental healthcare.’

The reliability / unreliability of psychedelic-induced recovered memories of childhood abuse

Then there is the question of the response of the guide, and MAPS, to Amy Griffin’s psychedelic-induced recovered memory.

We’ve come across many cases of people recovering memories of childhood sexual abuse, through psychedelic experiences. Are these memories literally true or not? That’s up to the person to decide. Sometimes they decide they are true, and sometimes they find evidence which confirms the truth - that could include someone else saying they were abused by the same person. Sometimes they decide it is a vision, not literally true, but perhaps containing some symbolic truth. Sometimes they accept they’ll never know for sure.

Given the fact psychedelic-induced recovered memories are sometimes literally true and sometimes not, therapists and guides need to step carefully in how they respond to these experiences, neither rushing to confirm someone’s memories nor rushing to deny them. That’s especially the case if the client decides to confront another person and publicly accuse them of violent sexual abuse.

During the ‘memory wars’ of the 1990s, there were many highly acrimonious law cases over recovered memories of childhood abuse between adults and their families. Some of those law cases involved MAPS-connected psychiatrist Bessel Van Der Kolk, who spoke as an expert witness in defence of adults accusing family members of abuse. Psychedelic therapy needs to tread carefully in this area, otherwise it risks being discredited scientifically and culturally.

There are cases of guides and healers who are too quick to confirm a client in the belief they were abused. Why would they do that? Sometimes, because they may have a naive view of psychedelics always revealing the literal truth or triggering an ‘inner healer’ who is always right. Dr Samuli Kangaslampi, who researches psychedelics and memory at Tampere University in Finland, writes:

The idea of psychedelics recovering repressed memories has a long history, and currently appears to be quite prevalent in some psychedelic, perhaps especially ayahuasca and MDMA, circles. It further often problematically combines with the belief that “the medicine will show you what you need to see”. Thus, people go into therapeutic sessions or ceremonies with the specific purpose of trying to recover memories of what happened to them (typically as small children) and some facilitators appear to encourage this. And when they do recover something, they are very convinced that what they now remember must be true.

The idea ‘psychological problems are caused by buried trauma’ has been widely spread in healing culture, thanks to the global celebrity of psychedelic therapists like Bessel Van Der Kolk and Gabor Maté. Psychedelics can sometimes amplify your cultural expectations. Drew Barrymore, for example, who interviewed Amy Griffin about her book, said in 2023:

I’m curious to examine why I’m not open to a relationship. I really think I have some serious shit buried. And I don’t know if it’s like I need to try an MDMA treatment or psilocybin as a way to get to some state where I could see things in a different way.

Sometimes, psychedelic therapists or guides are too quick to confirm people’s recovered memories as true because they were abused themselves. And sometimes, therapists or healers tell clients they were sexually abused because it gives them power over the client. Jorge Llano, a psychedelic Gestalt teacher that EI investigated, who faced multiple accusations of abuse from students, told several of his students they had been sexually abused as children, as a way of controlling them and isolating them from their families.

We don’t know if Olivia gave any prompting to Amy regarding her psychedelic experiences, but it’s a risk.

How about Rick Doblin, founder of MAPS? The NYT article says:

[Doblin] played down the reliability of memories retrieved with MDMA, saying they are often “symbolic.”“Whether it’s real or not — meaning whether the incident actually happened — from a therapeutic perspective, it doesn’t matter,” he said. “A lot of times people will develop stories that help them make sense of their life.” He added, “In the therapeutic setting, what Amy went through, whether it’s true or not, it has value because the emotion is real.”

Mr. Doblin said both that “frightening memories that people have pushed out of their mind come back under MDMA” and “you have to be somewhat dubious, I guess, about recovered memories.” (The day before this article was published, Mr. Doblin contacted The Times and insisted that he did believe Ms. Griffin’s memories were real.)

Did Doblin raise the possibility the memory could be real, or it could be symbolic? Rick told us:

We did mention to Amy that psychedelic-recovered memories could be symbolic. A big part of the book is Amy trying to figure out if the recovered memories actually took place or were symbolic. She was clearly aware that recovered memories should not automatically be assumed to be accurate reflections of historic reality. Amy’s healing was real, by her own account and those that know her.

Was the book really in Amy Griffin’s best interests? Were there other steps she could or should have taken first - like contacting the teacher and asking for a conversation? That’s what others have done when they recovered memories of abuse during psychedelic sessions (see this article). The book certainly helped to propel MDMA therapy to the front-pages as a ‘celebrity psychedelic infomercial’ as the New York Post put it. But this is a very successful, law-abiding person publicly admitting to taking an illegal drug and then sharing the rawest experiences of her life for the public. Was she in any way encouraged to write the book by ‘Olivia’ or Rick Doblin, who seems to have been quite involved in the editing process? Rick tells us: ‘MAPS did not mention writing a book to Amy or encourage her to write the book. That was her own idea’.

On guru-worship and psychedelic Rasputins in American high society

There is a broader point to make about the risk of underground guides in the world of high-net-worth spirituality. Some of the American elite has fallen in love with psychedelic drugs. There’s nothing wrong with that, and in fact, there’s one big benefit - they have helped fund psychedelic research and helped propel various psychedelic drug treatments to the brink of FDA approval, as well as helping to get guided psychedelic sessions legalized in several US states.

However, the elite’s love-affair with psychedelics has also led to the rise of a whole cadre of ‘shaman bros’ targeting ultra-wealthy people, offering them drug experiences at exorbitant prices often with very little safeguards.

More after the paywall.