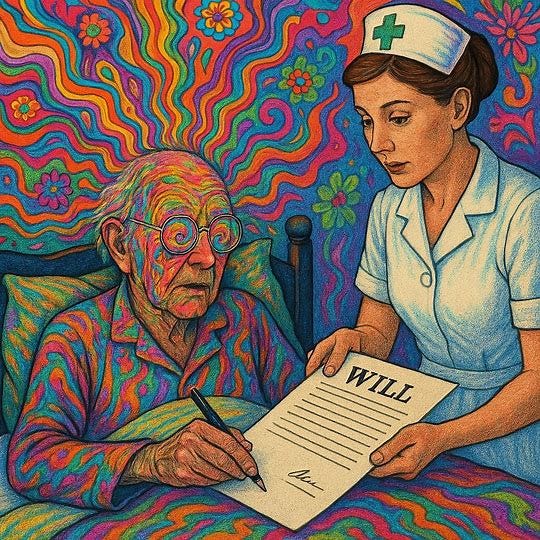

Undue influence in psychedelic palliative care

TL DR: don't accept bequests or donations from your psychedelic clients

Welcome to Ecstatic Integration, the newsletter of the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project. I’m Jules Evans, a writer who has written books on ancient philosophy, the history of ecstatic experiences, and spiritual emergencies. This Substack explores how / whether western societies can re-integrate ecstatic experiences wisely and relatively safely.

Psychedelics for end-of-life care is becoming a thing, and potentially, it could be one of the biggest ‘medical’ uses for psychedelics. While depression, PTSD or substance-abuse affect many of us, dying affects all of us, so psychedelic palliative care is potentially a very big market.

Psychedelics’ potential to improve people’s experience of dying was noted in the 1950s by Aldous Huxley, who took LSD on his death bed in 1963. If you think the Eleusinian Mysteries may have involved a psychedelic (academics aren’t sure) then ‘psychedelic-assisted dying’ goes all the way back to ancient Greece - the initiates of Eleusis, after drinking the secret potion, felt they could ‘die with a better hope’.

It’s exciting, then, that New Mexico passed a legal psilocybin program this year that, among other things, allows psilocybin for end-of-life care; that the US Health Department is considering rescheduling psilocybin to enable compassionate access for those with terminal cancer, and that psychedelic centres at University of New Mexico, Emory, NYU, Johns Hopkins and beyond are studying psychedelics’ potential to improve people’s quality of death. Psilocybin is already available for end-of-life care in Canada under its Special Access program, and ketamine is already used in palliative care in the US.

Still, there are ethical issues to be considered with psychedelic end-of-life care, some which have been briefly covered in some books and articles - see Davis et al 2025, or the new book Psychedelics in Palliative Care. One issue explored by Chris Letheby and others is whether psychedelic palliative care is providing consolation to the dying by giving them a ‘comforting delusion’ that there’s life after death.

Two issues I have not yet seen covered in this discussion are, firstly, the ethical risk of undue influence by psychedelic facilitators over the elderly or terminally ill for financial gain, and secondly, the psychological risk of hellish trips actually worsening people’s quality of death. Both of these risks are real and, I’m afraid, will certainly occur, so it’s worth discussing them before psychedelic palliative care becomes a big market. I’m not a lawyer, and the below should not be taken as legal advice.

Francis Bacon and the legal precedent of ‘undue influence’

The idea of ‘undue influence’ goes back 400 years and has appeared in hundreds of cases involving care-givers - sometimes medical, sometimes spiritual - being accused of manipulating vulnerable people to get hold of their fortunes after they die.

The term was first used in a law case in England in 1617, adjudicated by none other than Lord Francis Bacon, inventor of modern science and, at the time, Attorney-General and Lord High Chancellor of England under James I. The case that came before Lord Bacon, Joy versus Bannister 1617, involved an old rich man called George Lydiatt, and a young woman called Anne Bannister, wife of Thomas Bannister. Lydiatt, on his death, left a fortune to the young woman of £3000, which is roughly a million dollars today. The will was disputed by the niece of George Lydiatt, Elizabeth Joy, who hoped ‘that the deed and will might be voided on the ground that Lydiatt had been induced to make them by undue influence, threats and cruelty of the female defendant’.

The niece, Elizabeth, claimed that

the said George Lydiatt , being an old man about the age of eighty years and being weak of body and understanding and having a great estate of goods and lands to the value of £3,000 and more, was drawn by the practices and indirect means of the said Anne to give up his house here in London and to come and sojourn with her at her house in the country, and she having him there did so work upon his simplicity and weakness and by her dalliance and pretence of love unto him and of intention after the death of her then husband to marry him, and by sundry adulterous courses with him and sorcery and by drawing of his affections from the plaintiff Elizabeth and other his kindred, telling him sometimes that they would poison him and sometimes that they would rob him, and that thereby she circumvented the said George Lydiatt and got from him at the first in gold plate and such a like matter of £1,000 or £1,500, and afterwards by her said practices caused him to make the said will whereby she got all his personal estate…and that after the said Anne had gotten the said George Lydiatt to make the said will and conveyance and thereby had possessed herself of his whole estate, she neglected such attendance of him as she had used before and used him in a most cruel manner.

Lord Bacon ordered that the will be ‘dampened and made void for ever’. He also ordered that Anne Bannister be brought before the Star Chamber for further punishment - I’m not sure what that involved, but it doesn’t sound good.

That was the first ever legal use of the term ‘undue influence’, and since then it has been used in many cases in which the family of a wealthy person dispute a large bequest in a will, often made to a much younger person or to a priest or guru figure who the family say used ‘undue influence’ over the deceased to manipulate them to get their wealth. Usually, the person accused of ‘undue influence’ is in a care position - an assistant, carer, nurse or chaplain etc. Other factors which make an accusation of undue influence more likely to succeed in court include:

Age - the elderly are particularly susceptible

Isolation of the victim

Terminal diagnosis of the victim

Dependency of the victim on the carer

Diminished mental capacity of the victim

Substance use - especially if the person accused of undue influence uses drugs to control the victim and diminish their capacity for autonomy

Some of the tactics the perpetrator of undue influence might use include:

Isolating the target from their family and poisoning their relationship with them

Moving into their home

Controlling the flow of information between the victim and the outside world

Emotional manipulation - love-bombing and threats

Encouraging dependency on them

Fulfilling multiple roles in their life - ‘lover’, assistant, executor of their will, controller of their foundation and so on

Controlling them through drugs or other mind-control tactics - this is the key issue for the nascent psychedelic palliative care market

I’ll give two more case studies, one from a Victorian sex-cult, and another more recent example involving ayahuasca, a violent spiritual mentor, and a disputed million-dollar will, before considering how psychedelic therapists and organisations can protect themselves from the charge of undue influence.