The psychedelic industry's entity dilemma

Talk about them, or don't talk about them?

The psychedelic industry faces a dilemma. What should it say about entities?

The industry wants to go from the New Age fringes and become a normal, insurance-refundable part of western healthcare. And it’s doing pretty well at that objective.

However, psychedelic drugs reliably lead to entity encounters, and that’s not normal for western healthcare. And we’re not just talking about ‘mystical experiences’ or ‘inner healers’. We’re also sometimes talking about negative or malevolent entities.

As I wrote in this piece on negative entity encounters, a 2015 survey of 800 psychonauts by Fountonglou and Freimoser found that 46% of ayahuasca-takers reported ‘encounters with suprahuman or spiritual entities’, as well as 36% of DMT-takers, 17% of LSD takers, and 12% of psilocybin-takers. In a Johns Hopkins survey by Davis et al in 2020, 2561 people said they encountered entities while under the influence of DMT. They usually described these entities as a guide or helper, but 11% described the entity as a ‘demon’, ‘devil’ or ‘monster. For 78% of people, the entities were experienced as ‘benevolent’ or ‘sacred’, but 16% felt they were ‘negatively judgemental’ and 11% felt they were ‘malicious’. In Bouso et al’s 2022 paper on adverse ayahuasca events, which used data from the 11,000-respondent Global Ayahuasca Survey, 14.9% reported feeling ‘energetically attacked or a harmful connection to the spirit world’.

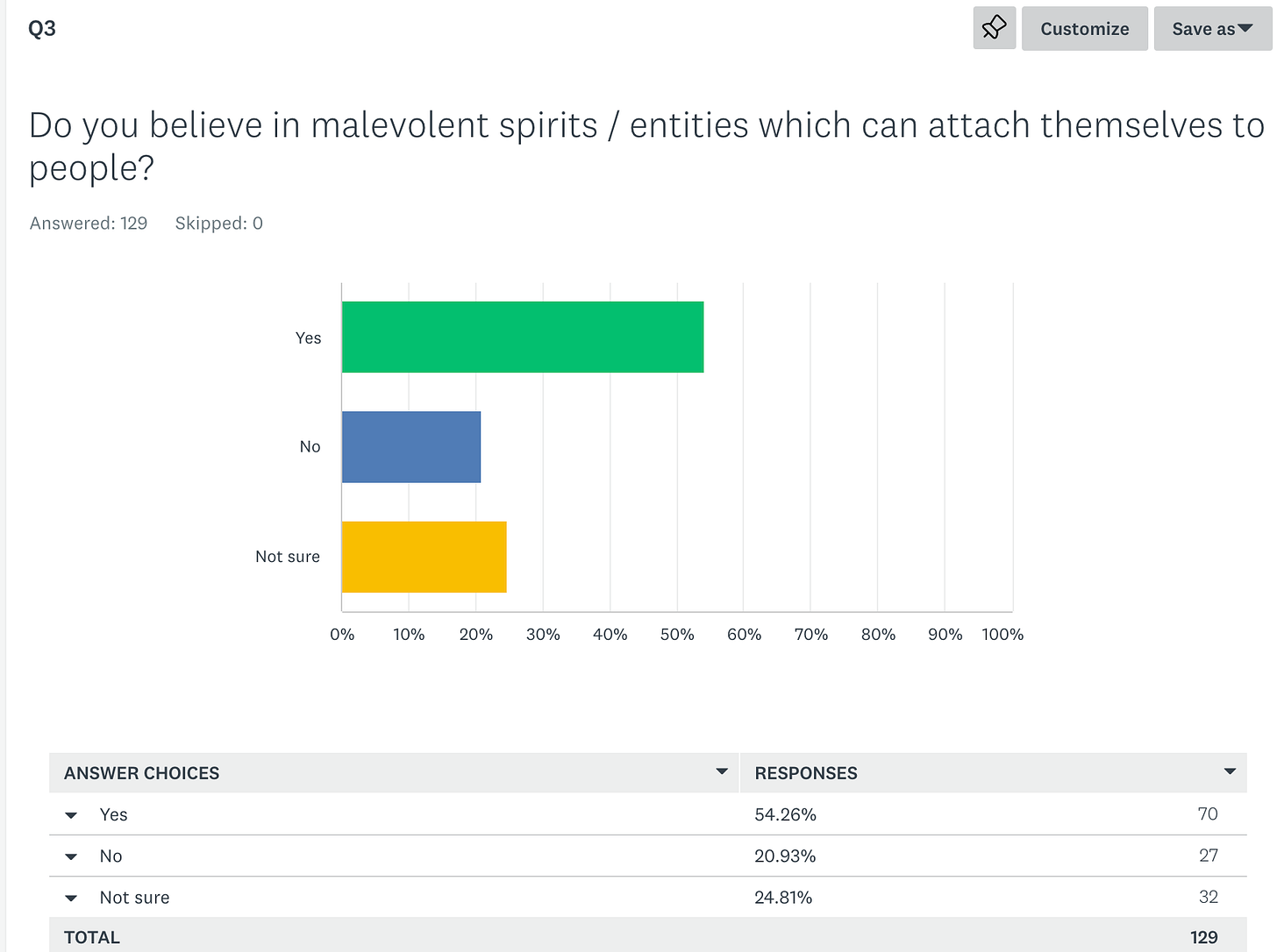

In a survey I did of 129 people who work with psychedelics (the full results of which are shared below) 72% said they believed in the existence of entities that one can encounter on psychedelics, and 55% said they believed in the existence of malevolent entities.

So here is the dilemma:

Should the psychedelic industry talk about entity encounters, including the risk of malevolent entity encounters or even spirit possession? Should it inform clients, customers and patients about this aspect of psychedelic experiences? Should psychedelic guides be trained in how to protect clients and themselves from malevolent entities?

Yes or no?

If you say ‘yes’ to those questions, then it becomes difficult to see psychedelic medicine ever moving from the New Age subculture to mainstream healthcare without a revolution in the western worldview. It’s hard to imagine the FDA including ‘risk of spirit possession’ in its labelling. And I think it would be off-putting to many potential ordinary-Joe consumers, if you told them ‘take this pill and there’s a good chance you might encounter benevolent entities, but perhaps a one-in-ten chance they could be malevolent’. Who’d want to go in the ocean if 10% of the fish attacked you?

Alternatively, you could say ‘no’ to these questions and do what the psychedelic industry is doing publicly now: don’t mention malevolent entities.

When you welcome people to your luxury psychedelic retreat, don’t mention malevolent entities. When you send traumatized veterans to do ayahuasca and DMT in Mexico, don’t mention malevolent entities. When you make DMT and 5-meo-DMT into short-acting treatments for depression, don’t mention malevolent entities. When you train psychedelic therapists, don’t mention malevolent entities. When you lobby politicians or voters to make psychedelics legal, whatever you do, don’t mention malevolent entities.

Whenever you promote psychedelics, do pay lip-service to indigenous wisdom and assure the public that humans have used psychedelics for centuries, but don’t mention the core belief in shamanic culture – that psychedelics open us up to helpful and harmful spirits, so you better have a good shaman to protect you (and fingers crossed they’re not a brujo).

Anyone watching the starchy and bureaucratic European Medicines Agency seminar on psychedelics earlier this week, which brought together regulators from the FDA, Health Canada, the EU’s EMA and the TGA in Australia, would agree that it’s impossible to imagine policy makers and drug regulators discussing malevolent entities. It’s weird enough for regulators and policy-makers to be discussing ‘the mystical experience’ or the ‘inner healer’, let alone hell-experiences and demonic encounters. So it’s just not mentioned.

And there are very good reasons one might decide not to mention entities – ethical reasons, as well as commercial and political ones. You might think ‘we need to make psychedelic therapy evidence-based and help it become part of mainstream healthcare. We don’t want to foster superstition and empower self-appointed shamans to tell patients they have a demon within them’. Or ‘we don’t want to prime people to have a demonic encounter’. Or simply ‘we don’t know enough - or anything - about spirits / entities to discuss them, let alone teach about them.’ All good points.

Still…empirically, psychedelics do lead to entity encounters (12% of people who take psilocybin, according to one study), and people do sometimes report feeling energetically attacked by malevolent entities. So is there an ethical argument for discussing this publicly?

What do you think?

Here are the results of my survey, and after that, survey respondents’ interesting thoughts on the entity-dilemma.

(Under ‘Other’, the most popular responses were integration coach, trip-sitter, training instructor, trainee-therapist and retreat host).

I analysed the above results to see which modalities seemed to correlate with belief in malevolent entities - 68% of those who identified with Jungian / depth believed in malevolent entities, followed by 62% of ‘shamanic’, IFS and Somatic practitioners, and 55% of CBT practitioners (NB, these are just the 71 people who said they did believe in malevolent entities).

Finally, I asked respondents for their thoughts on the ‘entity dilemma’ - after the paywall, what psychedelic workers think on the topic. And check out this piece I wrote last year on this topic, as well as last week’s piece on the idea of ‘unattached burdens’ (ie malevolent entities) in IFS.