The passing of a psychedelic prophet

Roland Griffiths transcended the role of scientist to become closer to a sage.

Last week, Roland Griffiths passed away, the person who arguably kickstarted the psychedelic renaissance with his 2006 paper, ‘Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences’.

I didn’t know him well, but had some interactions with him, and he always seemed a kind and generous man. The only time we met in person was at Breaking Convention in 2015, when he gave a talk on how one dose of magic mushrooms reduces people’s fear of death. Is that, I asked him, because it made them believe in life after death. ‘At least it makes them more open to the possibility’, he replied.

That seemed pretty remarkable to me – a drug that reliably makes people more open to life after death. It prompted me to wonder if psychedelics could play a central role in a ‘religion of the future’.

In 2018, I wrote a piece for Aeon, called ‘Is psychedelic research closer to theology than science?’ The piece argued that psychedelic science often involves theological assumptions, and it used Roland’s psychedelic centre at Johns Hopkins as one example.

Roland’s early papers suggest that psychedelics lead to a ‘core mystical experience’, which can be found at the heart of all religions, a mystical experience which can be quantified and measured as to how ‘complete’ it is. This is closer to theology than science, I argued, and many scholars of mysticism would disagree with this perennialist philosophy.

The Johns Hopkins lab then ( I argued) subtly suggested this perennialist theology to their trial participants before, during and after their psychedelic experiences, and then they have a perennialist mystical experience which is taken as evidence for the original theory. This is what the philosopher Ian Hacking called a ‘looping effect’.

Roland didn’t agree with me, and we had a friendly back-and-forth on email. He didn’t like that I had suggested psychedelic science was quasi-religious, perhaps because this was one of the main problems with psychedelic science in the 1960s – figures like Timothy Leary shifted from academic scientists to spiritual gurus.

Roland came to psychedelic research through his own spiritual interests. He got very into meditation and spiritual growth 20 years ago, through retreats at places like Esalen. There, he met Bob Jesse, a key figure in northern Californian spirituality, who persuaded him to start doing academic research on psychedelics. Bob also persuaded Michael Pollan to write about Roland’s work.

Roland was very careful to keep the tone of his research sober and cautious, without too much religious enthusiasm. This was empirical science, he was a respectable academic scientist, this definitely wasn’t religion or Leary-style counter-cultural preaching.

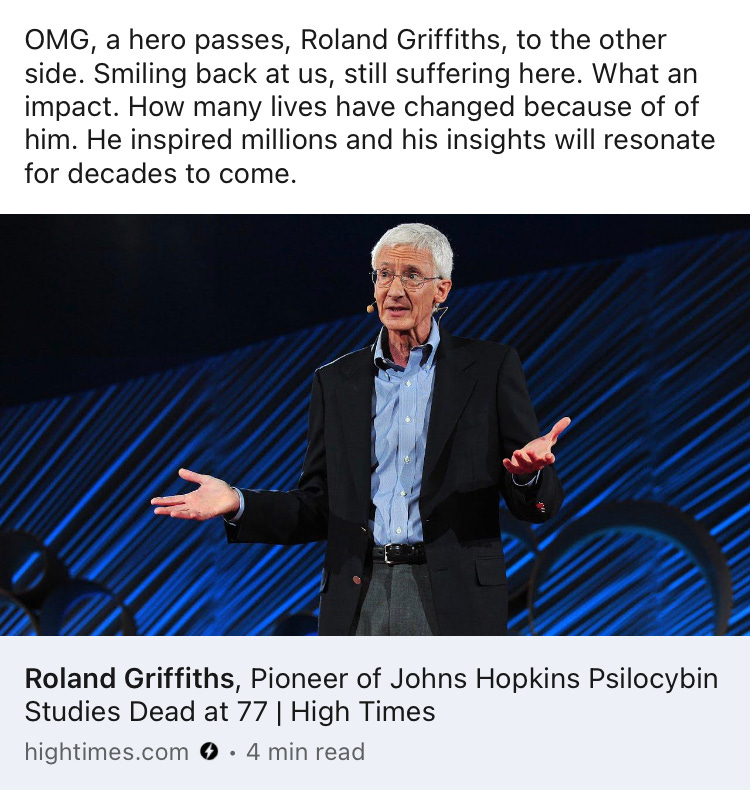

Yet psychedelic science always does seem to lead to religious enthusiasm, both in its researchers and the wider ‘psychedelic community’. The community responded to his death as they did to the passing of Tim Leary or Ram Dass - as the passing of a saint or holy man. That much was noticed by Leary’s son, Zach, who posted:

Here are some of the other public responses, which I share to show the depth of people’s veneration for this man.

‘His star burns eternal’, ‘a gentle giant of psychospiritual techniques’, ‘a hero passes’, ‘he will continue to support us from the other side’. Can you think of any similar response to a scientist’s passing, outside of psychedelic research?

Why is Griffiths so revered? His achievement was, firstly, political – he gave the study of psychedelics institutional credibility. In 2006, when he published his first paper on psychedelics, it was extremely hard to do psychedelic research. Now it’s much more normal and accepted. Roland opened the way for the burgeoning psychedelic industry in which thousands of people now make a living.

The second reason for people’s emotional response to Roland’s passing is spiritual.

Many famous scientists died this year - for example, John Goodenough, the inventor of lithium batteries. None of their deaths were greeted with the sort of religious response which Roland’s passing inspired. Why not? Because lithium batteries may help save the world, but they don’t inspire religious experiences. Paychedelic drugs do.

People take psychedelics, they have religious experiences, then they venerate the people they associate with these experiences - shamans, bands, gurus, doctors and scientists.

The sociologist Nicolas Langlitz calls psychedelic drugs ‘charismatogens’, precisely because of this effect. At one psychedelic conference, he saw an audience member literally kiss the feet of Albert Hoffman.

Psychedelics inspire religious enthusiasm, and psychedelic scientists often end up becoming closer to spiritual figures than orthodox scientists. This happened to Hoffman, to Humphrey Osmond, to Timothy Leary, to Betty Eisner, to Carlos Castaneda, to Stan Grof, to Samuel Widmer. And it still happens to scientists today.

In the last year of his life, as he faced his diagnosis of terminal cancer with incredible grace and wisdom, Roland increasingly transcended the role of scientist and moved closer to a sage or prophet. He appeared on Oprah in June, and told her that psychedelics reliably lead to three main insights: ‘we’re all interconnected, life is sacred, and this is emphatically true’. He asked: ‘How can we maximize such experiences, and how can that eventually change humankind?’

In a New York Times interview in April, he said: ‘If we look at the long range, this could be critical to the survival of our species’. At Psychedelic Science in Denver, in June, where he spoke three times and received standing ovations each time, he declared that psychedelics have ‘transformative potential for humankind’.

Why is this important? We have rapidly growing technological threats – nuclear war, biowarfare, AI. These are existential risks. I’ve come to believe that this line of research may be important to the survival of this species. We’re in a potential race here.

He told Lucy Walker, who made the Netflix documentary How To Change Your Mind: ‘You know how important what we are doing is, don’t you. It is a fight between good and evil, and we must fight to win’.

He did also warn of the ‘catastrophic risks’ of psychedelics - and I guess there was an ambivalence within him on the issue of adverse effects. He was very worried about them, but on the other hand, psychedelics could save the human race. The last time I was in touch with him was a couple of months ago, to arrange an interview on psychedelic risks and harms. Alas, time ran out.

His last act was the founding of a professorship in ‘secular spirituality’ - based on the three holy insights he suggested people often arrive at - all life is connected, all life is sacred, this is deeply true. He thought this spirituality might eventually change the world.

Is it a problem to turn empirical science into a spiritual mission? It depends who you ask. You could argue that every ground-breaking movement needs its enthusiasts, its visionaries, its utopians. I see a similar religious mission in mindfulness science or other medical interventions which hope to save the world. You can’t change the world with tepid scepticism alone.

However, Griffiths’ spiritual mission caused some consternation among less spiritually-minded colleagues. It’s an open secret in the psychedelic community that he disagreed with Matthew Johnson, another psychedelic professor at Johns Hopkins. There seem to have been two main reasons - one was due to internal Johns Hopkins politics, which I am not privy to. The other reason was Johnson’s concerns - going back to 2018 - about what he saw as the centre’s promotion of a spiritual vision.

Two weeks ago, before Roland’s death, Johnson gave a talk on psychedelic ethics, and said this:

I’m increasingly concerned about the degree to which these experiences can be used to shape metaphysical beliefs. Unless its for sacramental use in a religion, if you’re a psychologist or physician, it’s extremely important not to fill in the blanks on the big metaphysical questions on the nature of God or reality. Some people really believe they’re encountering God. Our role [as scientists] isn’t to deny any of that. It’s to let the patient make any determination. Otherwise there’s a chance to push people into cult-like behaviour. Even relatively mainstream researchers and clinicians can fall into the trap of playing guru. I’ve been in over a hundred sessions, and it’s humbling to be told you’re part of ‘the most meaningful experience of my life’. It can go to your head as a clinician. You can take advantage of that, in extreme ways or more religious cult-like behaviour, where the doctor becomes the guru or priest, and they’re the access to God, or even more subtle ways, where they’re held as the sage or oracle.

You probably have your own opinions on the tendency for psychedelic scientists to become ‘shamans in white coats’ as Michael Pollan called them. It may be good, it may be bad - it’s definitely a thing. What do you think of the phenomenon?

I personally feel some gentle scepticism about psychedelic spirituality and its fusion of science and theology. I agree with historian Mike Jay, who is wary of psychedelic scientists acquiring too much charismatic status - he contrasts that to the Native American Church, where there’s a ‘roadman’ for each ceremony but they’re not considered particularly special.

I’m also not sure you can build a stable ‘empirical theology’ based on psychedelics because the experiences are too variable and unpredictable. Roland insisted that people almost always arrived at his holy trinity of insights - connectedness, sacredness, truth. And this can ‘change someone enduringly in a positive direction’.

But anything psychedelics can do, they can also do the opposite. People have all kinds of weird experiences, and come away totally convinced they’re true. They come away convinced the universe is meaningless, that they’ve spoken to aliens, that they’re the worst person in the world, that they should invest all their money in crypto.

I wonder, therefore, whether psychedelics are too unpredictable and too risky to ever became the sacramental heart of a major global movement.

However I may very well be wrong.

If a stable psychedelic spirituality does emerge, Roland Griffiths will undoubtedly be seen as one of its prophets. And I hope no one minds me discussing some of these points in an obituary. That’s what academic discussion should be, after all - a discussion.

I’ll end by saying I find the academic study of these mystical questions fascinating, and I am so glad we can now discuss them without shame or stigma. Thank you Roland for helping to make that happen, for giving us all the chance to study this most interesting of topics.

And now, after the paywall, this week’s links on psychedelic and ecstatic harm reduction. All subscribers get access to our video library which includes the recent psychedelic safety seminar featuring Mike Jay and Andy Mitchell.