Steven C. Hayes on psychedelics and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

'The Third Wave was the revenge of the hippies'

This week, CPEP hosted a seminar with Steven C. Hayes, originator of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which is one of the more evidence-based modalities of psychotherapy. Hayes spoke about how psychedelics can enhance ‘psychological flexibility’ (the core concept in ACT’s model of human flourishing), how psychedelics inspired him, how the third wave of CBT was a ‘hippy take-over’, and how ACT can help those experiencing post-psychedelic difficulties. You can watch the seminar here.

The most important take-away that I got was the importance (for therapists and coaches) of focusing on therapeutic processes / active ingredients, while not getting overly fixated on particular theories or modalities.

Hayes said: ‘Every therapeutic concept sometimes needs to not be used, and sometimes will be harmful for particular people.’ One example he gave - mindfulness is helpful for many, but not always. It can make some symptoms worse for some people sometimes. Even cultivating acceptance, which seems a universally-helpful process, may not always be the right message at the right time for a client. ‘Trust your inner healer’ might be helpful for many clients in psychedelic experiences, but not all people at all times, especially if someone is dealing with severe post-psychedelic difficulties.

Don’t try to fit everyone into one theory or therapeutic modality. A process that might help one person in one situation might harm another. Just as ACT tries to promote ‘psychological flexibility’, therapists and coaches need ‘therapeutic flexibility’, not to become too set in their ways. That’s one take away. The other is ‘follow the data’. I’m impressed by how ACT has set about building up its evidence base over the last 40 years. Hayes said:

I’ve set up 1440 randomized trials on ACT now, second only to traditional CBT. There’s a new one every three days. Half of them come from lower and middle income countries, and no other approach could say that.

Compare that to, say, Gestalt therapy or Internal Family Systems. How many randomised-controlled trials of IFS are there? Two. How about Gestalt, which has been around since the 1950s? Again, two. Many of the popular approaches in psychedelic therapy are high on charismatic gurus - Claudio Narando, Stanislav Grof, Dick Schwarz - and low on data. Ditch the gurus, follow the data.

Brief intro to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

ACT is sometimes described as a ‘third wave cognitive therapy’.

The first wave was Behaviourism (1910s -1960s). Developed by Pavlov and then BF Skinner, Behaviourism suggests humans react automatically to stimuli, we seek pleasure and avoid pain. To help a person change, reinforce positive behaviour and punish negative behaviour. Thoughts don’t really come into it.

The second wave (1960s to 2000s) was Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, developed by Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck (who I interviewed and wrote about in my first book). Thoughts matter. Thoughts are judgements about the world and they provoke emotions. When people get stuck in emotional problems, they’re stuck in certain ways of thinking - cognitive biases, irrational thinking. Through Socratic inquiry, CBT aims to help people think more rationally. It also seeks to change their behaviour - encourage depressed people to be more active, anxious people to face their fears, and so on.

The third wave (2000s to 2020s) includes therapies like ACT, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy, Mindfulness-CBT, Compassion-focused therapy and Functional Analytic Psychotherapy.

These evolutions of CBT seek to change not the content of thoughts but people’s relation to the thoughts. So, for example, rather than Socratically disputing an irrational thought (‘is this true? Where’s the evidence? Could I be catastrophising? etc), third-wave approaches might encourage a client to observe the anxious thought without identifying with it, letting it arise and pass away. Not Socrates but the Buddha, you could say. Hayes called third-wave approaches ‘the revenge of the hippies’. Many of its founding figures were influenced by meditation or psychedelics.

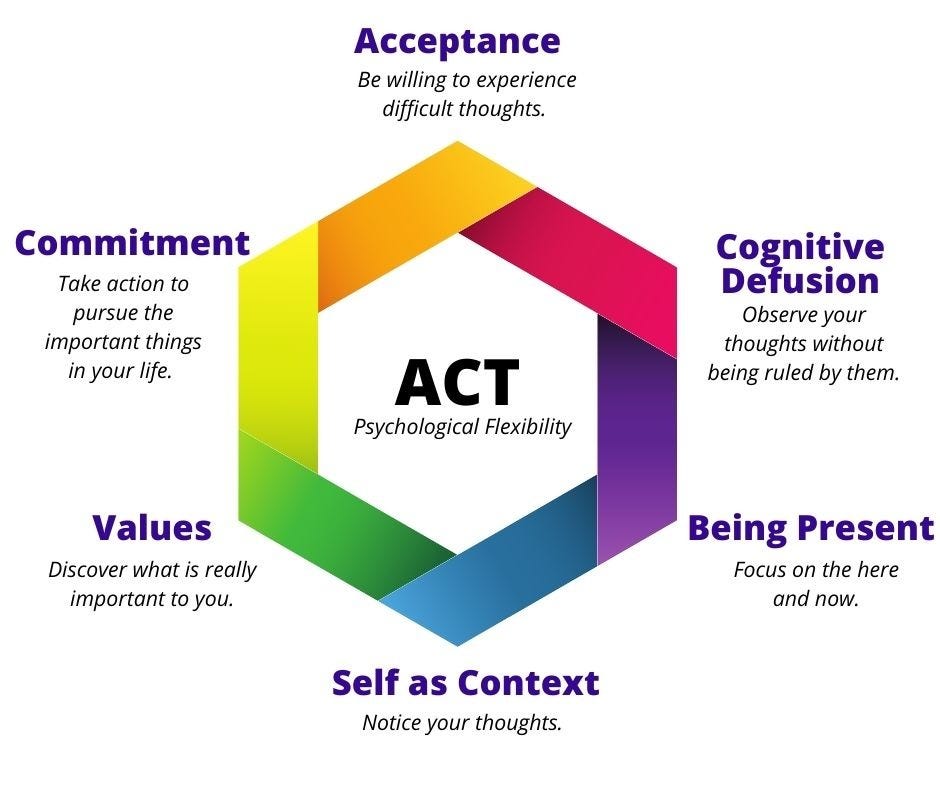

ACT seeks to help people achieve greater ‘psychological flexibility’, which Hayes and co-authors have defined as: ‘The ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior when doing so serves chosen values.’ The opposite of psychological flexibility is dogmatism and rigidity - we get stuck in maladaptive frames or stories about ourselves. In ACT terminology, we become ‘fused’ with a particular way of thinking, emotion or perspective, so that it completely dominates our attention, to our detriment.

We may also become more and more avoidant of certain experiences. In Hayes’ own case (recounted in his TEDX talk), he experienced severe panic attacks in his 30s, which sent him into a spiral in which he withdrew more and more from the world. Finally, he reached rock bottom, stopped running, and accepted what was happening to him. By switching from a posture of avoidance and escape to a posture of openness and acceptance, he discovered the anxiety and panic diminished.

Acceptance became one of six core therapeutic processes that ACT suggests reliably lead to psychological flexibility.

Another is Cognitive Defusion. This is the idea, at the heart of Stoicism and Buddhism, that you are not your thoughts, and the first step towards wisdom and maturity is to realize that and learn to observe thoughts and emotions instead of immediately identifying with them and acting on them.

This practice of self-observation relates to another core process, the ‘Self as Context’, which is similar to the idea of the noticing self in Eastern spirituality, Arthur Deikman’s ‘observing self’, or ‘the Larger Self’ in IFS. It’s the space or awareness in which thoughts and emotions arise and pass away. As we cultivate awareness, we can also learn to focus on the present moment (a key idea in mindfulness therapy and Gestalt therapy).

Finally, ACT emphasizes the importance of values and commitment. Psychology and psychotherapy have sometimes had a values-deficit, because science is supposed to be descriptive, not morally prescriptive (facts, not values). But meaning and purpose are important parts of flourishing and resilience. ‘He who has a why can cope with almost any how’ according to Nietzsche. You only need to read about wars or parenthood or professional sports to discover humans can tolerate very high levels of discomfort and suffering if they are pursuing what they see as a higher goal.

At the same time, psychologists can clumsily import their own values into their psychological theory, as Abraham Maslow did with humanistic psychology, and as Martin Seligman did with Positive Psychology. Hayes said:

We should never have done what we did in Positive Psychology. Marty Seligman: ‘here are the virtues’. Oh, just shut up. Those are your values, dude. Go to another culture.

ACT lets people choose their own values, so it’s compatible with many different cultures (I noticed a lot of people from Latin America at the seminar, while there have been over 100 clinical trials of ACT in Iran apparently). How does a person decide if their values are ‘good’ and ‘true’? Well, that’s the limit of therapy, they need philosophy or religion for that next step.

ACT and psychedelics

ACT has been used in several psychedelic trials (many led by Jordan Sloshower at Yale) and there are papers on ACT and psychedelics by authors like Alan Davis, Roland Griffiths and Fred Barrett; Jason Luoma (a former colleague of Hayes at University of Nevada) and Brian Pilecki of Portland Psychotherapy Clinic; and Rosalind Watts of Acer. Luoma and Watts adapted ACT for their ACE model (Accept, Connect, Embody). And here’s a paper Hayes co-authored on psychedelics and ACT, which he discusses in the video.

Some of the possible therapeutic mechanisms for psychedelic therapy match on to ACT’s hexagram of processes contributing to psychological flexibility.

A psychedelic experience can (on a good day) enhance ‘cognitive defusion’, cognitive distancing, de-habituation, relaxed beliefs, the loosening of rigid schema, thereby creating a space for people to observe their entrenched beliefs, habits, emotions, relationships or life-events from a new perspective. It can ‘reduce the domination of literal language, of problem-solving language, of the self-narrative and its neurobiological correlates’, in Hayes’ words.

On a good day, psychedelics can also enhance the sense of the present moment, what Alan Watts called the ‘eternal now’. They can enhance acceptance and non-avoidance of difficult experiences or emotions. Ros Watts noted that, during the Imperial College psilocybin trial (Psilodep),

participants described psilocybin sessions as an extended lesson in letting go of resistance and instead welcoming long suppressed painful emotions in the service of pursuing a richer, more meaningful life. This appeared to lead to a greater acceptance of their own experience along with a connection to themselves and others, both during the “trip” and in the months afterwards. Despite the absence of any therapeutic content related to t Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the trial, it was remarkable how similar participant experiences were to the therapeutic goals [of ACT].

Finally, psychedelics can lead to new or enhanced values and a strong commitment to a better life. A good example might be iboga / ibogaine, and how its gnarly ‘life review’ can give people a strong motivation to stay off addictive drugs.

ACT and post-psychedelic difficulties

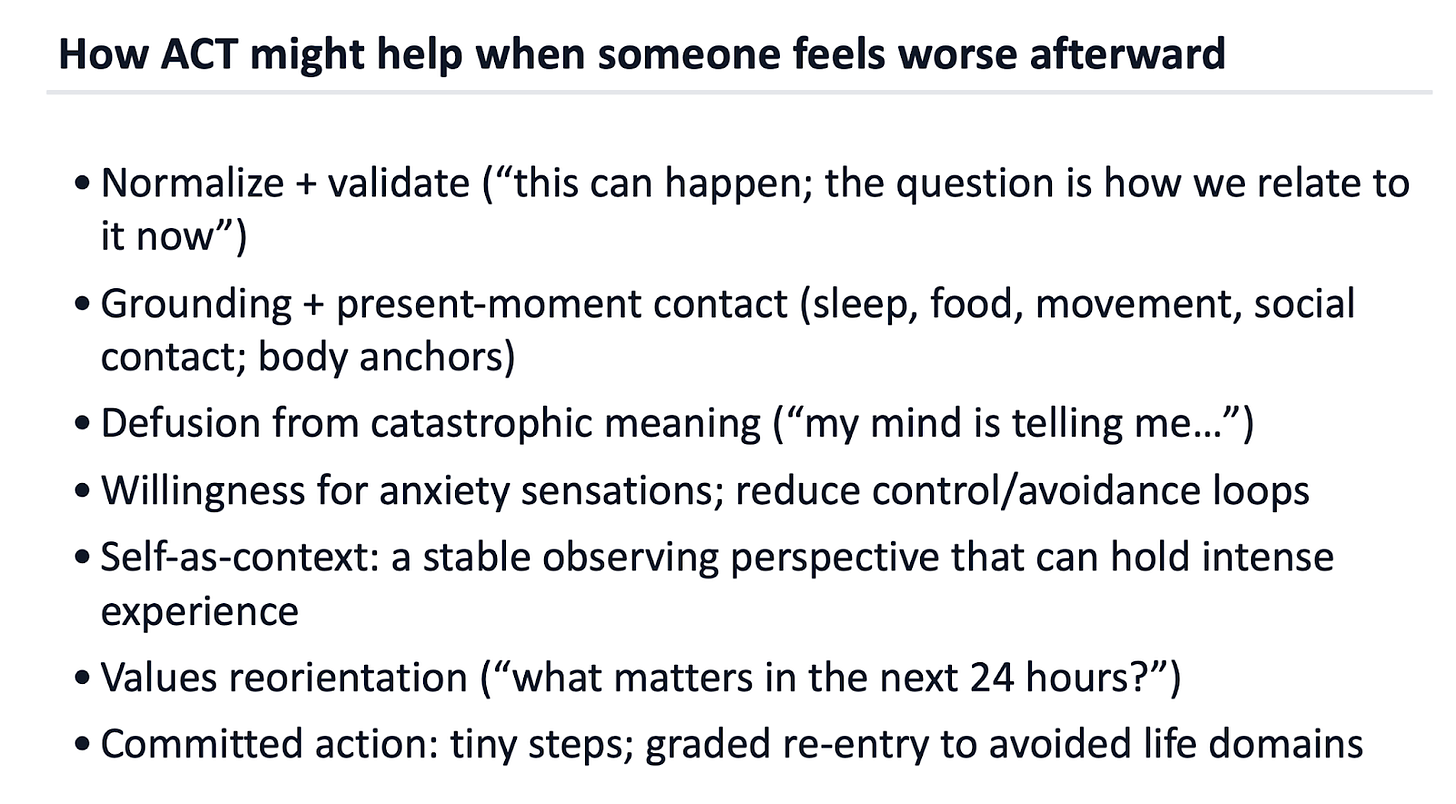

Of course, every one of these processes can work iatrogenically as well. Psychedelics can lead to mind-expansion and mind-contraction. They can lead to cognitive defusion, or make people totally fused with a certain story (‘I am permanently damaged’, for example). They can increase acceptance, or avoidance and phobia. They can enhance motivation or undermine it, or inspire fanatical commitment to kooky values (‘I should sell everything, move to the jungle, and become a Shipibo shaman’).

Hayes, an ‘old hippy’ whose wife used to work in the Grateful Dead harm reduction tent, is no stranger to psychedelic harm. ‘This powerful technology can be helpful but also hurtful’. He ended his brief presentation noting that ‘when psychedelics go awry, these same ACT processes can be helpful’. Certainly, I’ve noticed many people who come to CPEP mention some of these processes as helpful - cultivating acceptance of the situation and of unwanted symptoms; cognitive defusion from negative beliefs like ‘I’m permanently broken’; focusing on activities that give their life meaning rather than ruminating over symptoms, and so on. None of these therapeutic processes are unique to ACT, of course, one can find them in many modalities. But I appreciate the founder of a major therapeutic modality giving some thought to how to help those experiencing severe post-psychedelic difficulties - something that isn’t even mentioned in MAPS’ therapeutic manual.

OK those are the key takeaways. After the paywall, for those who want to go even deeper, we’’l hear about Hayes’ personal use of psychedelics, Hayes’ opinion on IFS, and how he thinks the psychedelic renaissance could screw it all up.