Psychedelic cults

We need to be able to tell the relatively benign from the toxic

We have two investigations ongoing that we will publish in the coming weeks that I’ve been working on for months, both are about ‘psychedelic cults’ (or should I say high-control groups that utilize psychedelics?). I find the topic of ‘cults’ fascinating, as do many others at the moment – witness the never-ending stream of cult exposes on Netflix, Amazon, Apple and other platforms, or the abundance of cult podcasts.

While we gobble up this cult content, we rarely ask why cults are a topic of such fascination at the moment. What do you think?

My theory is cult exposes provide an intoxicating cocktail of far-out spirituality and true crime. For lonely liberals in our highly atomised society, cults are both alluring (it sounds kinda fun to belong to a group of beautiful, spiritual, polyamorous people) and also repulsive (‘oh my god they’re all brainwashed!’). Cult exposes thus provide a voyeuristic double purpose – the viewer can imagine themselves a member of the cult from the safety of their lonely-liberal sofa, while also denouncing the cult as sick.

Despite our fascination with cults, the topic is undercovered and underresearched when it comes to psychedelics. There are barely any academic papers on psychedelic cults, besides this one and this one. But writers on the edge of academia have started thinking about ‘psychedelic cults’ – Jamie Wheal, for example, has spoken and written on the boom in psychedelic cults and how to try and keep them ethical and not destructive. The Conspirituality podcast has also featured episodes on psychedelic cults or alt-right red-pilling in psychedelic communities (check out this episode featuring Lorna Liana).

Now academic researchers are beginning to turn their attention to the topic. Nese Devenot recently discussed psychedelics and cult dynamics on cult-expert Steven Hassan’s podcast and also published this blog post on the Harvard Petrie law blog on why psychedelic bioethicists should take cult dynamics seriously. And Joseph Holcomb Adams and I are preparing a chapter for a new volume on psychedelic harm reduction looking at cult dynamics in psychedelic organisations.

I’ve now investigated a few culty organisations in the psychedelic space and see some fascinating similarities in them, but some important differences. But first let me make some points on competing theories of and approaches to cults.

What is a cult and are there benign cults?

First, what is a ‘cult’? Historically, it was a group of people passionately committed to a set of sacred values and practices, usually involving worship of a particular deity – the Dionysian cult, the Eleusinian cult, the cult of the Emperor and so on. In the 1970s Age of Aquarius, a ‘cult’ came to have a pejorative meaning - a new religious movement which used high-control tactics to recruit, indoctrinate and enslave its members. The classic 70s stereotype was cults seeking new members at airports - as parodied in Airpline:

Today, cult has broadened significantly to mean ‘a group of people passionately committed to a belief or activity’. The ‘Sounds like a Cult’ podcast has featured episodes on ‘the cult of pickleball, the cult of Taylor Swift, the cult of Instagram therapists and so on.

For my purposes, I’m interested in spiritual and therapeutic ‘cults’. As Steven Hassan and Jamie Wheal have both contended, spiritual or therapeutic ‘cults’ can exist on a continuum of benign / malignant, or ethical / unethical. Their place on this continuum isn’t static – a ‘cult’ can become more or less toxic over time. It might also be relatively benign at the fringes but incredibly toxic nearer the centre.

What makes a cult toxic is particularly how much control it exerts over its members’ lives, and how damaging the cults are to its members and to the public. Of course, the second issue is open to a lot of debate, and people within a cult may say they love it, and only realize how damaging it has been to them once they’re out of it.

What are some useful theories to help us make sense of destructive high-control groups? One of the first and still most important books on the topic was Robert Jay Lifton’s 1961 book, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism. Lifton researched the book during the Korean war, at a time when the US was wondering why its soldiers went on Korean TV to denounce United States. He helped to popularise the idea of how totalitarian societies control the minds and beliefs of their citizens, and how religious cults behave like micro-totalitarian societies. Another writer, Edward Hunter, coined the term ‘brainwashing’ for this, although Lifton preferred the term ‘thought reform’.

He identified eight techniques for ‘thought reform’:

1. Milieu Control. The group or its leaders controls information and communication both within the environment and, ultimately, within the individual, resulting in a significant degree of isolation from society at large.

2. Mystical Manipulation. The group manipulates experiences that appear spontaneous to demonstrate divine authority, spiritual advancement, or some exceptional talent or insight that sets the leader and/or group apart from humanity, and that allows a reinterpretation of historical events, scripture, and other experiences. Coincidences and happenstance oddities are interpreted as omens or prophecies.

3. Demand for Purity. The group constantly exhorts members to view the world as black and white, conform to the group ideology, and strive for perfection. The induction of guilt and/or shame is a powerful control device used here.

4. Confession. The group defines sins that members should confess either to a personal monitor or publicly to the group. There is no confidentiality; the leaders discuss and exploit members' "sins," "attitudes," and "faults".

5. Sacred Science. The group's doctrine or ideology is considered to be the ultimate Truth, beyond all questioning or dispute. Truth is not to be found outside the group. The leader, as the spokesperson for God or all humanity, is likewise above criticism.

6. Loading the Language. The group interprets or uses words and phrases in new ways so that often the outside world does not understand. This jargon consists of thought-terminating clichés, which serve to alter members' thought processes to conform to the group's way of thinking.

7. Doctrine over person. Members' personal experiences are subordinate to the sacred science; members must deny or reinterpret any contrary experiences to fit the group ideology.

8. Dispensing of existence. The group has the prerogative to decide who has the right to exist and who does not. This is usually not literal but means that those in the outside world are not saved, unenlightened, unconscious, and must be converted to the group's ideology. If they do not join the group or are critical of the group, then they must be rejected by the members. Thus, the outside world loses all credibility. In conjunction, should any member leave the group, he or she must be rejected also

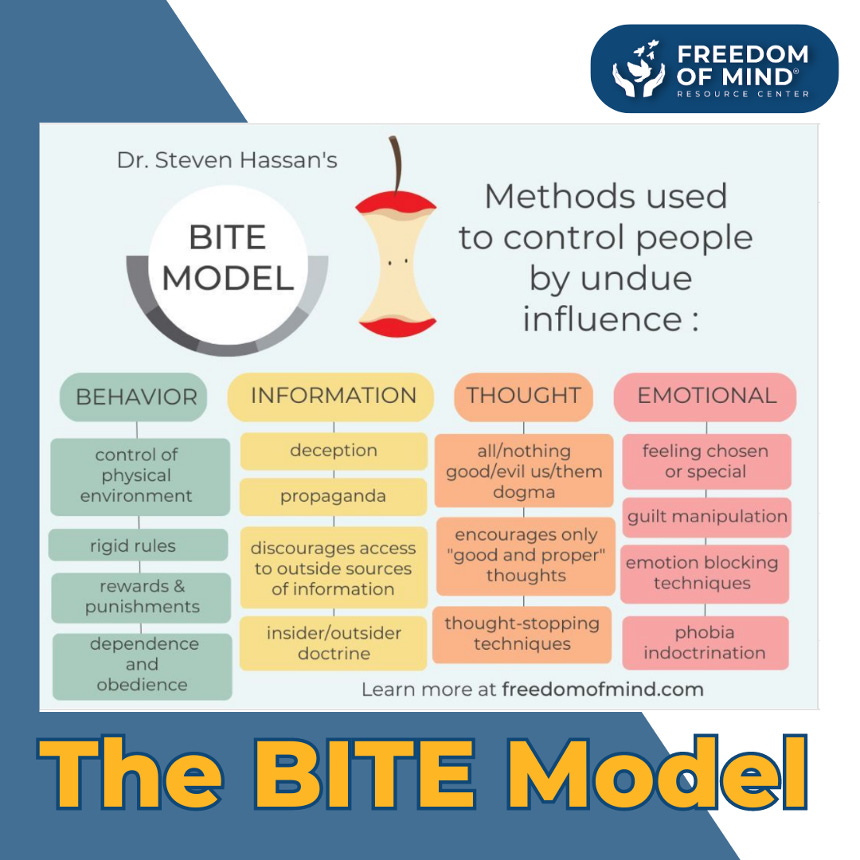

More recently ex-cult member Steve Hassan, founder of the Freedom of Mind Resource Centre, formulated the BITE model for how destructive cults control their members’ thinking. Here’s a handy graphic from his center:

On cults and anti-cults

There is a history to how western societies have thought about and tried to counter-act destructive cults. In the US, the state has largely steered clear of legislating or acting against some of the big cults like Scientology or ISKCON. There have been high-profile criminal cases bought against figures like Bhagwan Rajneesh and Keith Raniere (founder of NXIVM), but these have been on charges of criminal behaviour – immigration fraud, for example, or sexual abuse. There’s never been legislation passed explicitly targeting cults, as far as I’m aware, reflecting the US’ emphasis on freedom of religion and the central role that cults like Mormonism have played in US history.

Instead, the Anti-Cult Movement has tended to be grassroots, driven either by the families of cult members, or by evangelical Christians alarmed by the rise of New Age groups. The ACM has not been without controversy itself – in the 1970s, there was a market for entrepreneur vigilantes like Ted Patrick, who families would pay to kidnap their kids and subject them to intense and brutal deprogramming. Patrick was frequently arrested for his activities (below is a trailer for a documentary on him). Meanwhile the Christian anti-cult movement descended into a Satanic panic in the 1980s.

Today, figures like Steven Hassan have tried to put the anti-cult movement on a more professional, academic footing. They advise the FBI, give evidence in cases like NXIVM, and are just beginning to give their attention to the ‘psychedelic renaissance’.

In Europe, particularly in France, Spain and Italy, governments have taken a harder line on ‘cults’, passed laws against them, and established state bodies to police them, such as MIVILUDES, the French agency set up to counter-act cults in 2022, in the wake of the bloody Solar Temple Cult. Check out their latest campaign, it’s so French!

There is also a new anti-cult unit in the Spanish police, I understand, who have been shutting down ayahuasca groups like Inner Mastery. In France and Spain, there is a developed discourse against psychedelics, that they are ‘weapons of chemical submission’. Lists are also published of groups deemed ‘sects’, including some alternative health and spirituality organisations (even Holotropic Breathwork made the list one year). Generally, there is a much more secular, anti-religious and anti-New Age culture in Europe than in the US, and less respect for religious freedom. But there are some dissenting voices – in Spain, ICEERS has sought to defend ayahuasca organisations against police persection and their labelling as ‘cults’, while in Italy, Massimo Introvigne, founder of CESNUR and editor of the website Bitter Winter , has disputed the term ‘cult’ and instead suggested ‘criminal religious organisation’ – any religious organization that breaks a law should be prosecuted, and there’s no need to bring the contentious word ‘cult’ into it, he argues.

That’s some initial theory and recent history on cults. Now let’s turn to psychedelic cults. There are hundreds of new psychedelic churches popping up all over the world, some of them are culty, and some of them will be toxic high-control groups that damage the lives of their members. We need to be able to spot them. Here are some initial thoughts.

Initial thoughts on ‘psychedelic cults’

1) Not all ‘cults’ or cultish organisations are the same.

There is a spectrum of control – from low-control to extremely-high control – and different organisations will be at different places on that, and might shift over time. Toxic cults tend to be high-control at the center and low-control at the periphery – they tend to show one face to new entrants and another to long-term members.

Groups labelled ‘cults’ can be very different. For example, many of you might have seen the Love Has Won documentary. This group, famous for having mummified its leader after she died, has been widely labelled a cult. But it’s not a classic hierarchical pyramid cult. On the contrary, the leader of the cult – Amy Carlson, or Mother God – was arguably the main victim of it. She declared herself God on the internet, and then various people turned up to worship her, and she couldn’t really get off the stage, despite her best efforts. She died through mercury poisoning.

Or take MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Science. It has some of the features of a cult - charismatic leader, utopian mission, group-think, a tendency to dismiss side effects, and some questionable fundraising habits. But this isn’t a toxic cult in the sense of ‘high control group’ as far as I can see. It’s a somewhat cultish organisation which is relatively benign (depending on what you think of psychedelic therapy).

I’ve written about AWE, the psychedelic training school, which ticks some of the boxes of cult – charismatic leader who claims supernatural powers (Igor Llano), intense group exercises, intense loyalty to the organisation, dismissal of criticisms, intense hostility to those who leave or criticize the programme. It’s also got something of the pyramid structure of organisations like Landmark, in so far as students are often recruited as teachers. But it is mainly an online school, so it can’t really be classified as a high-control group yet, unlike the therapeutic school founded by Igor’s father Jorge Llano – at Jorge’s school in Bogota, students and staff would attend seven days a week and it had much more of the classic characteristics of a toxic high-control group.

Sowilo, the dangerous 5-MEO-DMT retreat centre in Mexico I wrote about last year, also had some of the aspects of a cult – charismatic leader who claims supernatural powers (French fraudster Bruno Cluzel), use of high doses of psychedelics to overwhelm followers. But it wasn’t exactly a high-control group, as most people escaped Sowilo after a few damaging days. Perhaps it was on its way to becoming a cult near the end – Bruno started to talk about ‘the family’, and suggesting long-term students transfer huge amounts of money to his bank account. Still, it was far from an organized totalitarian high control group.

Finally, I’m researching an ayahuasca school in Latin America, which ticks more of the boxes of a destructive cult. It has a charismatic leader who claims supernatural powers, and who uses psychedelics to control and manipulate his followers, while also sexually abusing them and demanding vast sums of money from them. Sounds like a toxic cult. Nonetheless, it’s not a cult in the sense of well-established totalitarian religion.

In other words, there are many different types of ‘cult’ and cultish organisation, and one needs to be careful when using the term.

2) The hook

Toxic high-control cults lure people in with a bait – it might be the promise of healing, or the attainment of spiritual power, or belonging to a loving family. There is a big promise. In the therapeutic community I’m writing about in Latin America, it was ‘you’ll be healed and become a great healer yourself’. In the shamanic cult, it was pretty similar – you will be healed and become a great healer. There is often an appeal to the vanity of the follower and their desire to be special and different. But the appeal is also to the loneliness and desire to belong.

3) The leader’s supernatural powers

Part of the hook is the allure of the leader. They usually claim some extraordinary powers – wisdom, insight, enlightenment, perhaps paranormal abilities like telepathy, healing touch or the ability to control spirits. These powers mean they know you better than you know yourself – so you need to trust them and surrender completely. It also means you’re frightened of them - they could turn their supernatural powers on you. A cult leader will be constantly testing your ability to surrender. They’re like a stage hypnotist, finding the members of the audience who are most suggestible. Really, much of the secret of founding a cult is theatre and stage-craft – the ability to fool people that you’re some highly superior being.

4) Every member becomes a prison guard

I have been interviewing people who have been in destructive cults for years, even decades. I sometimes ask, why did you stay so long? There are complicated reasons – they were conditioned to, of course, like beaten animals too afraid to run away. But one of the things that draws people into groups and keeps them there is their need for belonging. The cult becomes their new family. And then traumatized people trauma-bond to the new family, and defend it from any attack like they were defending their actual family. They are desperate to keep the organisation going because they are so emotionally and financially invested in it, it would be too awful if it were all a lie. In a totalitarian state, everyone becomes a prison guard. I don’t think this is sufficiently appreciated – cults aren’t simply one evil psychopath at the top, they involve complex social dynamics reminiscent of the Stanford Prison Experiment, in which the group polices obedience as much as the leader.

5) Cult leaders have a lust for power

Nonetheless, you do see similarities in the figures who end up as cult-leaders. They are clearly dark triad individuals – narcissistic (they think they are the greatest humans alive, want to be worshipped, and can’t ever accept being wrong), Machiavellian (they are masters at reading and manipulating other humans), and psychopathic (they don’t care about ruining other people’s lives). They construct their own little world where they are gods. And they’re often very bright, talented people, who may have genuine spiritual gifts, but they waste their abilities constructing and policing their little kingdoms because they are themselves victims of their narcissism and lust for power over others. They are themselves enslaved.

After the paywall, five more thoughts on psychedelic cults