How Huxley and Osmond's friendship shaped psychedelic culture

Plus a rare recording of Aldous on acid...

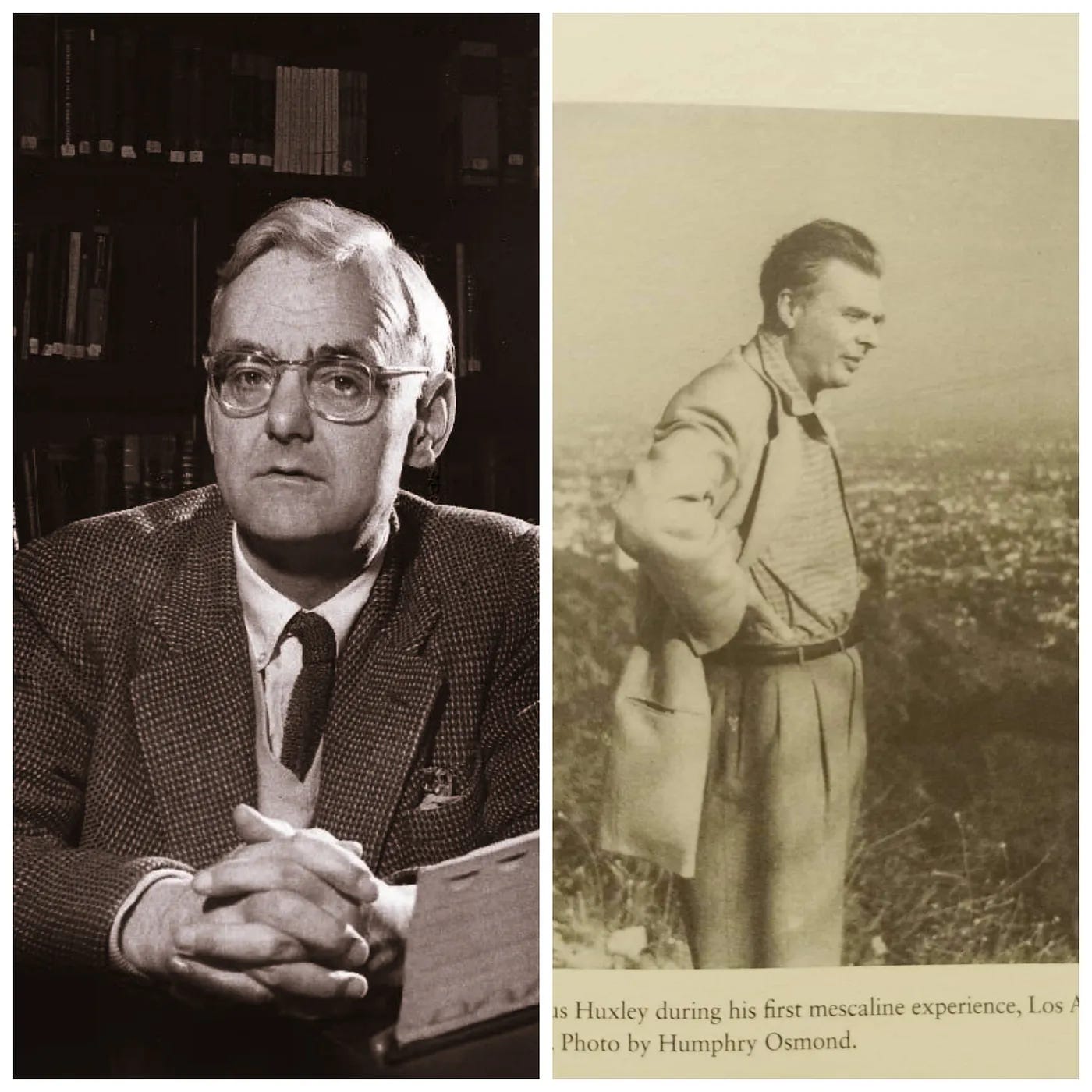

At 11am on the 4th of May, 1953, English author Aldous Huxley was given 4/10 of a gram of mescaline by the British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, who he had invited to his house in Los Angeles for that purpose. Aldous has since become celebrated as the great prophet of psychedelics, but today I want to celebrate his friendship with Humphry Osmond, who was with him on that first trip, and took the photos of Aldous tripping, shown above.

When they met, the 35-year-old Humphry was excited and awed to meet Aldous, who at 58 was one of the most famous novelists in the world. Humphry meanwhile was a British psychiatrist working in Weyburn Mental Hospital in Saskatchewan, Canada, where he experimented on his patients with LSD and mescaline as possible cures for alcoholism. He was also interested in whether psychedelics might uncover the chemical cause of psychosis, via a substance such as adrenaline. Aldous read one of his papers on mescaline and invited him to visit next time he was in LA, and to ‘bring some of the stuff’ with him for Aldous to try. Humphrey eagerly agreed, although he was worried he might go down in history as the man who sent Aldous Huxley mad. Aldous’ wife Maria was sceptical of the encounter. What if they didn’t like the young psychiatrist? ‘We could always pretend to be out’, Aldous suggested.

Luckily, Aldous had a good trip, and felt he had finally found the mystical experience he had been seeking for two decades, ever since he converted to perennialist mysticism circa 1930. He, Maria and Humphry all got on very well, and May 4th 1953 was the beginning of a friendship that would last until Aldous’ death in 1963. He and Humphry wrote hundreds of pages of letters to each other — most of them Humphry writing to Aldous — in which they discussed psychedelics and their potential role in civilization.

These letters (which have been published in the excellent book Psychedelic Prophets) and this dialogue helped to shape western culture’s understanding of psychedelics — indeed, Aldous and Humphrey coined the word ‘psychedelic’.

Up to that point, psychedelics had been described as ‘hallucinogens’ or as ‘psychotomimetics’ — because scientists (including Humphrey) were primarily interested in these drugs’ ability to mimic the effects of psychosis. Aldous, however, took a much more spiritual view of the chemicals, and suggested they needed re-branding. He always had a thing for advertising jingles, and suggested “phanerothyme,” from the Greek words for “to show” and “spirit,” with the jingle: “To make this mundane world sublime, Take half a gram of phanerothyme.” Instead, Osmond suggested “psychedelic,” from the Greek words psyche (for mind or soul) and deloun (for show), and quipped, “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, take a pinch of psychedelic’. The ‘phanerothymic renaissance’ doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

The author and the psychiatrist who reframed our relationship to ecstatic experiences

Their decade-long conversation was arguably far more wide-ranging and culturally-sophisticated than today’s psychedelic renaissance. They weren’t obsessed with psychedelics, for one thing, but saw them as one of many routes to a realm of non-ordinary or mystical experience, which can also arise spontaneously, especially in childhood. Osmond wrote:

it seems likely that the mescal world etc. is a potential realm of experience always open to us. Clearly in childhood when we know we are much more plastic the potentiality of this experience is likely to be much higher. In our culture and in most cultures to a more or less great degree adaptation to the “real” world is essential for survival. Those who take that potential path and stray any distance along it have great difficulty in getting back again.

Aldous brought a deep historical understanding to the topic of visionary experience, and argued that western civilization had marginalized and pathologized mystical experiences from the reformation to the present day, leading to a taboo around such experiences. Humphry agreed, writing:

the great industrial societies of the West do not know how to cure the sickness of the soul. Largely because they have banished mystical experience which is the gateway into otherness — even the few shreds of such experience which most of us have are unrecognized and unavailed. Raw experience cannot be classified or interpreted and frequently ends in madness. Yet these experiences, even the ghosts of them, are as necessary to us spiritually as vitamins are physically.

The two hoped that psychedelics, in opening up the ‘doors of perception’, could transform our relationship to non-ordinary states of consciousness, including states now deemed ‘psychotic’. Osmond (who by this time was head of a large psychiatric hospital) wrote:

Of course I agree that many of our “sick” people would not be “sick” if we valued their experiences, they would be explorers of the other, but…the schizophrenic person had his experiences entirely devalued. I am not sure how much certain experiences can be sustained even in the most accepting society; visions of Hell and Heaven must never be easy to endure even with the prayerful support of one’s fellows. It will be much less easy with their scornful, uncomprehending and brutal antagonism. I think we must do two things simultaneously, i) try to find some way of alleviating their experience biochemically, and ii) gather enough scientific understanding of the door into the many walls that we can appreciate and cherish mentally ill folk.

It’s interesting to look back and see how different psychedelic research was in the 1950s to today. There were some therapeutic studies of psychedelics for alcoholism, depression and schizophrenia; there were many military and CIA-funded studies of psychedelics’ potential as a weapon or truth-drug (Osmond himself did some work for MI6 and the CIA). But the principal focus of non-military research was informal experiments in Californian living rooms by the intellectual and cultural elite — people like the novelist Anais Nin, writer Gerald Heard, and the US stateswoman Clare Booth Luce. Humphry and Aldous agreed that the main focus of psychedelic research should initially be its impact on the elite. Osmond wrote that ‘the most gifted should be studied first. To study psychedelics on immature, inadequate or sick people is to lose most if not all of their great and indeed extraordinary possibilities’. He added in a later letter

Naturally as a scientist I am greatly interested in the huge variety of phenomena and the splendid possibilities for therapeutic use, not simply to heal the sick but as a prophylaxis. But I am not blind to the fact that this pursuit, though admirable, if continued unthinkingly might obstruct even higher achievement…It seems clear however that a society which could induce the higher levels of spiritual insight in say 0.01% of its population, plus some understanding and recognition of the nature of mind in many of the rest, would be very different from our hagridden, gadget bedevilled panicking world.

Their plan was to do ‘a series of recorded mescalin interviews with 50–100 really intelligent people on various professions and occupations….Einstein, Jung, Graham Greene and AJ Ayer’. Osmond thought:

If we can build up a group of gifted people who have had transcendental experiences and then get them together, I think that there is a reasonable chance that they might find some way of passing on this experience and giving some chance to those who only have vague inklings of it or the splendor and terror that exist just around the corner. So far as I know nothing like this would ever have happened in the West before — the drawing together of gifted people who have had astonishing experiences

This was very much a Modernist elitist endeavour, comparable to Gurdjieff’s gathering of ‘remarkable people’ or Herman Hesse’s league of Castalia. Alas, it came to nothing — Aldous and Humphry never raised any funding for their research proposal. Aldous was surprisingly bad at pitching for funding. He also had a plan to research psychedelics and Human Relations with Alan Watts, but that couldn’t get funded either.

Psychedelics and the paranormal

Another early focus of Humphrey and Aldous’ research, which is almost entirely absent from today’s research landscape, was psychedelics’ effect on paranormal powers like telepathy. They took part in attempts at ‘group mescalinization’, or developing a group-mind on psychedelics. This was probably the influence of their friend Gerald Heard, who had been trying to develop that sort of telepathic group-mind for 20 years through meditation. Osmond wrote:

It must be clear that if we can develop a form of group experience independent of words, and this seems possible to Al and me, then long range telepathy between members of such a group should be possible at a later state.

Both Aldous and Humphry were friends with a renowned psychic medium — Eileen Garrett. She communicated (or claimed to) with Maria Huxley after her death, and also took part in a psychedelics and paranormal research conference which Humphrey chaired in 1959 (photos below). Eileen was godmother to his youngest daughter Fee (his son, Julian, was named after Aldous’ brother, while his dog was called Mescalina).

A new psychedelic religion

Humphry and Aldous thought psychedelics would transform psychiatry as much as Freud’s discovery of the unconscious. But their true potential would be bigger than that — they would be at the centre of a new religion.

After the paywall, how Aldous and Humphrey thought the Native American Church could be a model to replicate, how they thought psychedelics tempted users with power, why they worried about psychedelic hype, and why mystical trips became more common on the West Coast than the East thanks to the ‘Huxley effect’. PLUS I found a recording of Aldous tripping…