Existential confusion after psychedelic experiences

What's it like, what helps? Insights from our research

Before the 18th-century enlightenment, ecstatic experiences enjoyed a central place in Western Christian culture, but they were then increasingly marginalized and pathologized as delusional, stupid and dangerous - a topic I explored in my book The Art of Losing Control. Now, they are slowly returning and becoming more normalized, thanks to the rising popularity of practices like yoga, meditation and psychedelics. However, the re-integration of ecstatic experiences into modern culture is a messy and decades-long process. The main aim of this newsletter is to track that process and try to help it.

Michael Pollan’s 2018 book, How To Change Your Mind, has played a significant role in this historical process, perhaps as significant as Aldous Huxley’s 1954 book The Doors of Perception. Both these books opened the Overton Window and made ecstatic experiences (specifically, drug-induced ecstatic experiences) seem less scary and more enticing. Both led to a sharp uptick in the number of people looking to try psychedelics for spiritual healing and growth.

But while Huxley once suggested that as much as 30% of psychedelic experiences could be hellish, Michael Pollan’s book and Netflix series sold a much more chilled version of the drug-induced mystical experience. Consider the cover of his book - someone gently swinging from a cloud. It looks like a very mellow ketamine trip. No dragons, hell-realms or bewildering questions there.

Pollan’s work on psychedelics was inspired by the work of Roland Griffiths at the Johns Hopkins psychedelic centre. He and his colleague Bill Richards argued that psychedelics reliably lead to something called ‘the mystical experience’, which people could expect to be unitive (giving them a sense of oneness), sacred, deeply positive in emotion, noetic (filled with meaning), transcending time and space, paradoxical and ineffable (hard to explain to others). This idea was shared by other leading centres, like Anthony Bossis’ team at NYU.

These centres’ research on psychedelic-induced mystical experiences assured people they would make them more open, less anxious, more connected, more filled with meaning, and less afraid of death. A trip would be one of the most meaningful and positive experiences of your life - perhaps the most meaningful. Who could resist such a pitch?

Now it is true that some people do have psychedelic experiences that neatly tick off the characteristics of ‘the mystical experience’. They come away feeling less anxious, more connected, more filled with meaning, and so on. Their worldview can also shift, from materialist to spiritual, and they may feel less afraid of death as a result. This does indeed occur.

However, it does not always occur. Not everyone has mystical experiences - apparently they are less common in Europe than in the US, apparently for cultural reasons (Europeans are less spiritual than people from the US). And even when people do have mystical / religious / ecstatic experiences, they are not always unitive, they don’t always feel deeply positive in mood, they are not always easy to understand or integrate into your life. Time is certainly altered - but that can make people feel they spent an eternity in hell.

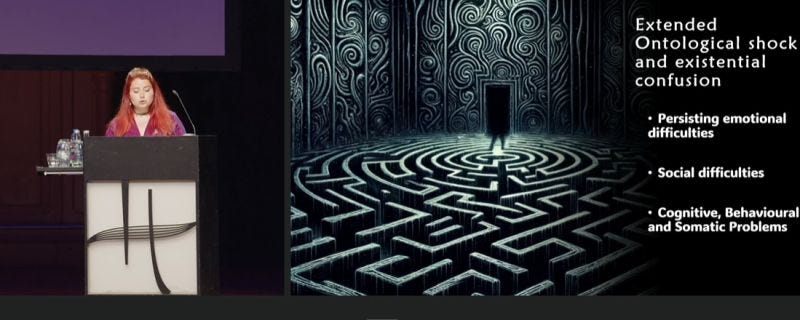

Psychedelic experiences, in other words, can lead to profound existential confusion and ontological shock, which can leave people feeling bewildered, overwhelmed and traumatized - and these symptoms can last for years or even decades. For some, this phase of bewilderment might lead to a new worldview which they come to see as more true and more valid than their pre-trip worldview. But the journey from the old world to the new world can be long, confusing and frightening. And some questions are never neatly answered.

Our research on post-psychedelic existential distress

The Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project published a survey in October 2023 of over 600 people who reported post-psychedelic difficulties lasting longer than a day. We asked them to describe their difficulties then we themed them into eight broad categories and 60 sub-categories. One of the main categories of difficulty was ‘existential / ontological difficulties’ - 42% of responses fitted into that category. We also created the sub-category ‘existential struggle’, in which we put any responses that mentioned struggling with meaning and purpose after the psychedelic experience. 17% of responses fit into that sub-category, making it one of the most common forms of extended difficulty. Here’s one example:

I entered the experience believing that my experience is the literal real external world. The experience contained me living out my worst fears, the deepest possible shame. Other experiences so bizarre and dreamlike I could not make sense of them. These memories left a legacy of confusion about what deeper model of reality to use, and repeated experiences of flipping between these models at different times.

We recently undertook a follow-up survey (yet to be submitted to a journal) of 159 people who reported post-psychedelic difficulties, asking them to describe specific symptoms, how long they lasted, how severe they were, and what specifically helped with each specific symptom, to try and pick apart some of the findings of the first survey.

As part of this follow-on survey, we asked people whether they had ever experienced ‘an external sense of struggle to comes to terms with the meaning of life or the nature of existence after the psychedelic experience’. 103 people out of the total of 159 said they had experienced this difficulty. On average, they said they experienced this difficulty for around 17 months - significantly longer than respondents said they experienced other forms of post-psychedelic difficulty, like increased anxiety or social disconnection.

To dive deeper into the phenomenology of post-psychedelic existential confusion, we undertook a qualitative study of 26 people who described symptoms like it in our 2023 extended difficulties survey. Pascal Michael and I were part of the team who did interviews and then analysed transcripts for themes, and the final paper was lead-authored by Eirini Argyri of Exeter University. It’s available as a pre-print here. What is post-psychedelic existential confusion like, what might cause it, and what did people say helped them cope with it?