Ethical dilemmas facing psychedelic schools

And one school's plan to create a professional complaints procedure for clients of their graduates

Thanks to everyone who helped with this piece, especially Joy Krecke, and various sources who spoke off-the-record.

While the psychedelic industry awaits legality, two parts of the industry are already making money - the underground, and psychedelic training companies. There are now, by our count, at least 160 organisations offering some sort of psychedelic training or education course.

That includes mainstream universities like UC Berkeley, Exeter, UPenn, Maastricht and Columbia; more New Age universities like CIIS, Ubiquity and Naropa; psychedelic organisations like MIND Foundation, Open Foundation and Chacruna; specialist training organisations (some of which also run trials) such as Fluence, Synthesis, Vital, Numinus, Clerkenwell Health and the Institute for Psychedelic Therapy; all the way down to smaller organisations like the Alien Institute or Myco-Method, whose teacher taught out of her van.

And then there are even smaller and less official organisations - a shaman might take on apprentices, for example, or a retreat centre may take on interns or offer short facilitator-training retreats. We guestimate there are at least another 100 smaller and less formal courses or training / apprenticeship programmes.

These courses offer a variety of content and aim to create different sorts of expertise - some are targeted at academic researchers in STEM or humanities; others target licensed therapists or other healthcare workers (nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, hospital chaplains); others aim to create psychedelic coaches, or facilitators, shamans, trip-sitters or harm reduction workers. Some courses may specialize in specific jurisdictions, or specific substances. Students might be drawn to them for different reasons too - career opportunities, personal healing, spiritual growth, lifelong learning, or a desire for community and family. One training company literally advertizes for ‘wounded healers’.

Most training providers only started offering courses in the last three years, and this young industry faces ethical and practical questions. Some are well-known and already much-ruminated:

How can different sorts of experience and wisdom be recognized, passed on, and certified?

How much training, and what sort of training, is necessary to guide someone during and after a trip? How about if the client has a serious mental illness?

Can you be qualified or even certified as a shaman?

Should therapists and psychiatrists have personal psychedelic experience? And so on.

For consumers interested in psychedelic education, there is a very basic question. How can you pick a good trainer? How can you verify their qualifications? In the absence of clear professional standards, transparency or industry maturity, the field is ripe for charlatans, who pretend to be more experienced and qualified than they are, and who perhaps falsely claim to be a shaman or ‘medicine man’ or veteran guide. People might have years of underground experience and still be unsafe teachers, never having faced consequences for their bad behaviour.

Linden Schaffer, a consultant for wellness industry, wrote recently:

Navigating the world of psychedelic education is a challenging endeavor, particularly when much of the space currently operates underground. While personal stories and testimonials can be incredibly compelling, it's important to remember that one teacher or programs success with an individual doesn't guarantee the same experience for everyone. Some of the questions I'd ask before embarking on a training such as:

What is the background and experience of those teaching?

How transparent are they about their practices and their pricing?

What will I be prepared to do when the training is over?

Courses now typically stress the importance of ethics and safety. However, courses themselves face ethical dilemmas, as do any people teaching on them. Here are four key ethical dilemmas which I want to discuss today:

Are courses giving false confidence to people that there are good economic opportunities from this work?

Are they implicitly or explicitly training people for the underground, and if so, what are the ethics of that?

Are graduates likely to be in-over-their-head with psychological or physiological emergencies or boundary violations?

Are some training schools themselves potentially unsafe and unethical, in which case, are guest faculty behaving unethically in working with them?

These are questions I’m asking myself as someone engaged in this field. I taught a class for Synthesis back in 2021, before the retreat company went bust last year (the training part of the company was taken over by Retreat Guru and is still running). I now teach a module on post-psychedelic difficulties for Clerkenwell Health’s course and we’ve been asked to present our research for other courses. We need to consider that some graduates of some courses might be working in the underground, and some courses might be actively supporting the underground . My main concern with underground work is (a) guides are not typically trained for deep trauma work (b) they don’t typically face career consequences for negligence or misconduct (c) because it’s illegal they have a personal incentive to ghost clients if they get into difficulties after trips (and this happens a fair amount alas).

I am curious how training companies are dealing with these questions, and have asked a few of them for this piece. One solution being developed by the Synthesis Institute (now owned by Retreat Guru), is the development of an ethics code for graduates and an independent ethics board, to which clients of Synthesis graduates can complain if they feel harmed. That is potentially an interesting step towards the sort of professionalization that other wellness industries (yoga, coaching, acupuncture, Reiki, even tantric massage) introduced years ago. I wonder if some sort of official complaint procedure could help raise standards and improve consumer safety in the underground - although as we’ll explore there are complications when the work is still mostly illegal.

Four ethical dilemmas

Are courses giving false confidence to people that there are good economic opportunities from this work?

Wellness training programmes can sometimes be pyramid-scheme Multi-Level Marketing-type rackets. If you think about, say, the coaching industry, or yoga training, or the essential oils market, sometimes the main consumers in industries are people training to be providers. These training industries sell the dream of a certain lifestyle, but the economic reality for their graduates is often much harder.

How about psychedelic training? This is a very young market. CIIS was the first to launch a facilitator training course, back in 2015, followed by Fluence in 2019. Most other courses launched around 2021, 2022 or early 2023, at the height of the ‘shroom boom’, when optimism and media hype were high, new legal markets were appearing in Oregon, Colorado and Australia, the ketamine industry was booming, MDMA was predicted to be FDA-approved in 2022, psychedelic stocks were hot, and funding was easy to come by, even for companies with no obvious revenue stream.

A young market - a few of the leading providers (not an exhaustive list by any means)

We’re in a different moment now. There could be delays for FDA approval of MDMA therapy. Australia’s expensive legal psychedelic medicine market has few customers prepared to pay the $20k or so for treatment; Oregon’s expensive legal psilocybin market is under-used by consumers and over-populated by facilitators; the psychedelic stock market has flat-lined and companies like Numinus are almost out of cash. There are retreat companies, but they don’t make much and tend to offer unpaid internships. There are hundreds of ketamine clinics in the US and Canada, but they tend to employ nurses to plug the IV in. One industry consultant says: ‘My concern is, with the path to medical approval taking a while, a lot of these new graduates will turn to the underground for work opportunities.’

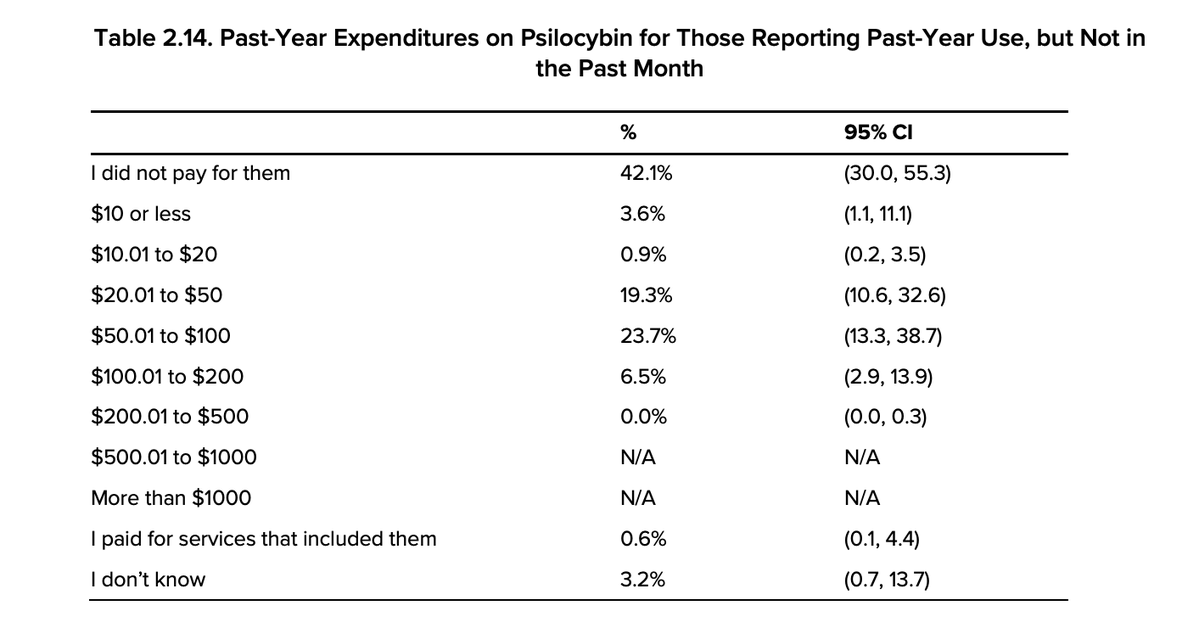

But how many earning opportunities are there even in the underground? Judging by the Rand Institute’s recent report, most people prefer to get their psychedelics for free, or under $50, and to take them with friends. Is there definitely a market for guided trips?

Psychedelic graduates face economic challenges, therefore - there is not much of a clear and viable legal-regulated or even illegal-unregulated market yet. Courses need to be upfront about the limited earnings payback at the moment, preferably before students shell out tens of thousands for courses. And graduates should not put all their eggs in one basket. As Paul Austin, founder of the Psychedelic Coaching Institute, wrote recently:

Are courses implicitly or explicitly training people for the underground, and if so, what are the ethics of that?

The legal regulated psychedelic market barely exists, so graduates who have paid tens of thousands for psychedelic training courses are likely to offer their services in the underground. At the moment, courses deal with this in one of four ways. 1) They explicitly tell their students not to work illegally. 2) They turn a blind eye. 3) They tolerate their students working in the underground and some teachers do it too. 4) They actively train their students to work in the underground, and may even sell them the drugs as well.

I asked some people who work on leading training courses what they think of their graduates potentially working in the underground. They all spoke off the record: