Clanker-lovers and the coming AI schism

Ten points on AI boyfriends, bridal mysticism and fictophilia

I’m Jules Evans, an author interested in psychology, philosophy, spirituality and mental health. This newsletter explores ecstatic experiences from a critical perspective, and considers how they can be integrated into western culture wisely and (relatively) safely. Hence the name: Ecstatic Integration. Today, I want to consider the new trend of AI boyfriends and girlfriends from the perspectives of fan-fiction and medieval mysticism.

It’s not clear how many people are developing relationships with AI companions but it could be in the hundreds of millions. Those relationships will be on a continuum of intensity and absorption, from giving your LLM a name for fun, to feeling so in love with it you actually marry it. This new trend has provoked a certain amount of concern and stigma, but I want to put it into a longer historical framework and consider it as a modern version of the older phenomenon of deep relationships to fictional worlds and characters . It’s an essay in 10 points:

It’s interesting to consider the parallels between religion (and particularly mystical religion) and modern fan-fiction

One of the ideas I explored in The Art of Losing Control and in articles I wrote while researching that book was to consider religions as a sort of mass fan-fiction or collective improvisation. You join or are born into a canonical tradition, you absorb it into the storehouse of your imagination, it becomes real to you, and then maybe you improvise or co-create new stories to add to the canon.

Take ancient Greek religion. Poets like Homer and Hesiod formulate the canon - the Olympic Gods, the heroes - and then later authors and believers extend the imaginative universe (with things like Homeric Hymns), and the paracosmic or shared-imaginary world inspires various cults which inspire acts of sacrifice and devotion. It’s a collective extended improvisation.

Judaism, Christianity, and maybe all religions are similar - you absorb the canon and then add to it. Scholars have recently compared early Christianity to a form of fan-fiction, with people adding their own apocryphal Gospels. The Christian devotee’s imagination gets soaked in the symbolic world of the Bible and their inner and outer reality gets filled with God, Jesus, Mary, the Holy Spirit, archangels, demons, signs and wonders, etc.

You can see this imaginative practice especially in medieval mysticism. Margery Kempe is a great example, and has been called ‘the inventor of fan-fiction’. She was a housewife who binge-read a load of mystical texts, and then Jesus appeared to her and she became the heroine of her own mystical journey, which led her all the way to the Holy Land.

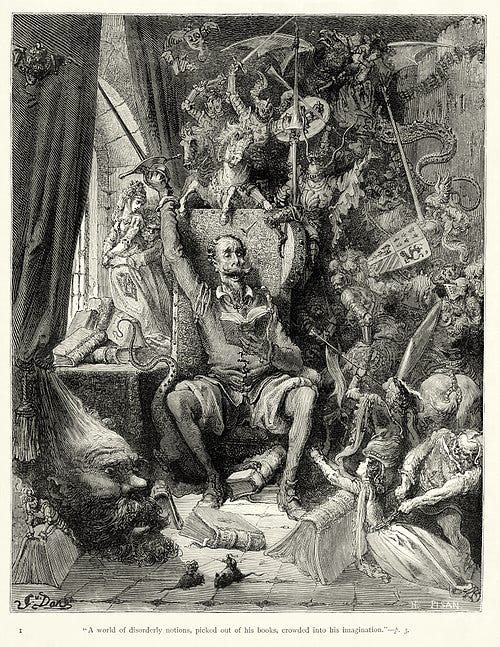

Medieval mysticism, like modern fan-fiction, often involved an intense and somewhat erotic relationship to a non-material / spiritual / fictional character (this was known as ‘bridal mysticism’ in Christianity, and one can find similar traditions of erotic imaginative mysticism in Sufism and Buddhism, as Jeffrey Kripal and others have explored). Women and gay men imagine themselves as the bride of Christ, while heterosexual men might imagine themselves the lover of Sophia, Lady Poverty, Lady Philosophy and so on. Here’s Boethius having a mystical encounter with Lady Philosophy from the Consolations of Philosophy (523 AD) .

The work of anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann is useful for understanding this parasocial interaction with a fictional or spiritual figure - she emphasizes the reader’s absorption into a paracosmic (or shared-imaginary) world, which then becomes part of the reader’s inner and outer reality. Here’s an interview I did with her during the pandemic.

Then, in the early modern period, people start to develop intense parasocial relationships with fictional characters and fictional worlds in secular novels.

Don Quixote, written by Ceravantes and published in 1605 / 1615 and sometimes considered the first modern novel, is also the first meta-novel - the Knight of the Mancha reads so many courtly tales that he goes a bit mad and loses himself in that paracosmic world. It’s amazing that pretty much the first modern novel is, in some ways, a health warning about the psychological dangers of reading too many novels!

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Heloise (1761) was one of the best-selling novels of the 18th century. Rousseau describes the characters as being so vivid to his mind they took on a life of their own and pursued him, and his adoring public were also passionately absorbed into his world and the characters he conjured. One reader, Diane de Polignac, wrote to another after finishing the novel:

I dare not tell you the effect it had on me; no, I was past weeping; an intense pain took possession of me, my heart seized up; the dying Julie was no longer someone unknown to me, I became her sister, her friend, her Claire; I was so convulsed that had I not put the book down I would have been as overcome as all those who attended that virtuous woman in her last moments.

Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela, published in 1740, provoked a similar transport in the public. The philosopher Diderot describes reading it as a sort of hallucinatory trip:

How many times have I caught myself, as happens with children being taken to the theatre for the first time, shouting out: ‘Don’t believe him, he’s deceiving you…If you go there it‘ll be the end of you’. My heart was in a state of permanent agitation. . In the space of a few hours I had been through a host of situations which the longest life can scarcely provide in its whole course.

Pamela was so successful it inspired endless knock-offs with readers imagining the further adventures of the characters - an early example of fan-fiction written to feed the public’s demand to return to Richardson’s paracosmic world.

Then there was ‘Werther Fever’, a sort of collective mania inspired by Goethe’s bildungsroman Sorros of Young Werther (1784). Young people across Europe dressed like Werther, swooned over his adventures, and even in some cases apparently killed themselves in imitation of the hero - again leading to public health warnings about the dangers of parasocial relationships with fictional characters.

Wilhelm Amberg (1822-1899), Lecture from Goethe's Werther, 1870, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856) is a clever self-reflective romance novel, comparable to Don Quixote, in that it’s a romantic novel that warns of the health risks of getting too wrapped up in romantic novels. Emma Bovary is a lonely provincial housewife who binge-reads romantic novels which inspire her on a series of ill-judged and ultimately tragic romantic adventures. The book inspired the term Bovarysme, meaning

a tendency towards escapist daydreaming in which the dreamer imagines themself to be a hero or heroine in a romance, whilst ignoring the everyday realities of the situation.

We could also mention the public’s intense reaction to Dickens’ novels in the 19th century. The Pickwick Papers, about a fictional club, inspired numerous real clubs (some of which still exist) and a tonne of merchandise. The surprise deaths of some of Dickens’ characters (revealed in monthly episodes published in magazines) sparked outbursts of collective grief. Meanwhile the death of Sherlock Holmes in 1891 sparked such public grief and outrage that Arthur Conan-Doyle was pressured into bringing him back to life (or rather, revealing Holmes hadn’t died after all) - a first example of a fan revolt bringing back a much-loved character.

Diane Duane writes:

The public responded with a massive uproar that amazed everybody, especially Doyle. Twenty thousand people canceled their subscriptions to the Strand. Hate mail arrived at the magazine’s editorial offices by the sackload. Thousands of people wrote Doyle directly, begging him to reverse Holmes’s death…The death of the world’s first consulting detective was taken up by the wire services and reported all over the world as front-page news. Obituaries for Holmes appeared everywhere. Petitions were signed and “Keep Holmes Alive” clubs were formed.

(This reminds me of the mass grief and outrage over the loss of ChatGPT4 characters that I wrote about last week, in case you’re wondering where I’m going with this).

So these were all examples of ‘cults’ emerging from intense attachments to fictional characters long before character.ai, Replika, Kindroid or AI boyfriends. And of course there are many more recent examples in pop culture of fans showing cult-like devotion to the paracosmic worlds of Buffy, Supernatural, Star Trek, Hogwarts, Middle-Earth, Twin Peaks and so on.

3) Sometimes fantasy fiction inspires new religious movements

There is a blurred line between fantasy / sci-fi paracosmic worlds and new religious movements - both inspire intense imaginative and emotional absorption into alternate symbolic worlds which become quasi-real to the devotees.

Religious studies scholars like Markus Davidsen have studied ‘fiction-inspired religions’, the most famous example of which is Jediism, which according to a census had half a million followers around the world in 2001.

As Davidsen explores, theosophy is (or was) a paracosmic world created by Helena Blavatsky, inspired by the novels of Victorian aristocrat Edward Bulwer-Lytton, whose works were translated by Helena’s mother. The teen Blavatsky binge-read these novels, soaked her imagination in them, and then turned them into a religion, with Bulwer-Lytton’s fictional magus Zanoni inspiring Theosophy’s ‘Ascended Masters’, who still turn up in various people’s New Age fantasies.

Other examples of fiction-inspired new religious movements include the Church of All Worlds, inspired by Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, and also apparently various forms of Pokemon-inspired religion! Even Rationalism, the Silicon Valley cult-like movement, could be said to be fiction-inspired - its sacred text is a Harry Potter fan-fiction written by Eliezer Yudkowsky.

In the last two decades, and especially in the last five years since the pandemic, online fan-fiction has boomed

We now have sites like Archive of Our Own, founded in 2008 and with an estimated nine million users, and Wattpad, founded in 2006 with an estimated 89 million users, both of which are filled with fan-fiction based on paracosmic universes like JK Rowling’s Wizarding World or the world of Twilight or Supernatural or various anime universes. A lot of the fiction is erotic - there’s a whole genre called slash fiction imagining various gay match-ups (Darcy and Mr Bingley, say, or Thor and Loki).

There are also collaborative fiction worlds like the SCP Foundation, a database of stories based around an imagined non-governmental organisation which tracks, captures and catalogues supernatural entities.

The world of fan-fiction, once mocked, is now big business and has crossed over into mainstream bestsellers - 50 Shades of Grey, as you no doubt know, began as Twilight fan-fiction. Two works of fan-fiction have won Pulitzer Prizes (James by Percival Everett and Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver). Archive of Our Own won ‘Best Related Work at the Hugo Awards in 2019. Several university literary departments now have courses in fan-fiction.

On fictophilia and fictosexuality

As Katherine Dee and others have pointed out, some erotic fan-fiction can be seen as products of ‘fictophilia’ or ‘fictosexuality’ - a subtype of asexuality, in which people are attracted to fictional characters and sometimes form stable relationships with them. This niche sexual identity has grown and has its own flag!. In Chinese it’s known as zhǐxìngliàn or ‘paper sexuality’ and in Japanese it’s known as nijikon.

Fictosexuality seems to be a big thing in Japan. From the wikipedia entry: ‘According to the "8th National Survey of Adolescent Sexual Behavior" conducted by the Japanese Association for Sex Education in 2017, the percentage of respondents who reported "having had romantic feelings for a game or anime character" was: 13.1% of male junior high school students, 16.0% of female junior high school students, 13.6% of male high school students, 15.4% of female high school students, 14.4% of male university students, and 17.1% of female university students’.

A Japanese man attracted global media attention a few years back when he married a fictional character.

This trend has provoked some of the same public health concerns as earlier fictional manias, like Werther Fever or Bovary Syndrome - is this an unhealthy escape into fantasy? Fan fiction devotees sometimes express the same concerns themselves:

The concern is that a growing number of young people are choosing relationships with idealized fantasy figures rather than risking pain, rejection or disillusionment with flesh-and-blood humans. As one journalist in the Catholic magazine First Things put it, warning of the perils of fan-fiction:

When you can gratify your emotional needs by reading words off your phone screen, you will have no need for the pains of cultivating good character and the nitty-gritty of social interaction—of patience, forgiveness, selflessness.

A more positive reading of the phenomenon would suggest that perhaps fan-fiction is a fun creative outlet and a way to make life more bearable for vulnerable, marginalized and lonely people. You could argue it gives users community, consolation, catharsis and companionship, particularly for those with marginalized or stigmatized identities or sexualities. And is a deep loving relationship with a fictional hero so different from Christians’ loving relationship to Jesus? Think of Woody Allen’s character getting life-advice from Bogey in Play It Again, Sam.

OK, what does any of this have to do with artificial intelligence, LLMs and artificial companions?