Can Opus Dei become less culty?

While the ailing Pope pushes for its reform, Opus' influence is rising in the US

This is a long weekend read. Make a coffee, fasten your thigh-chain, settle in and enjoy…

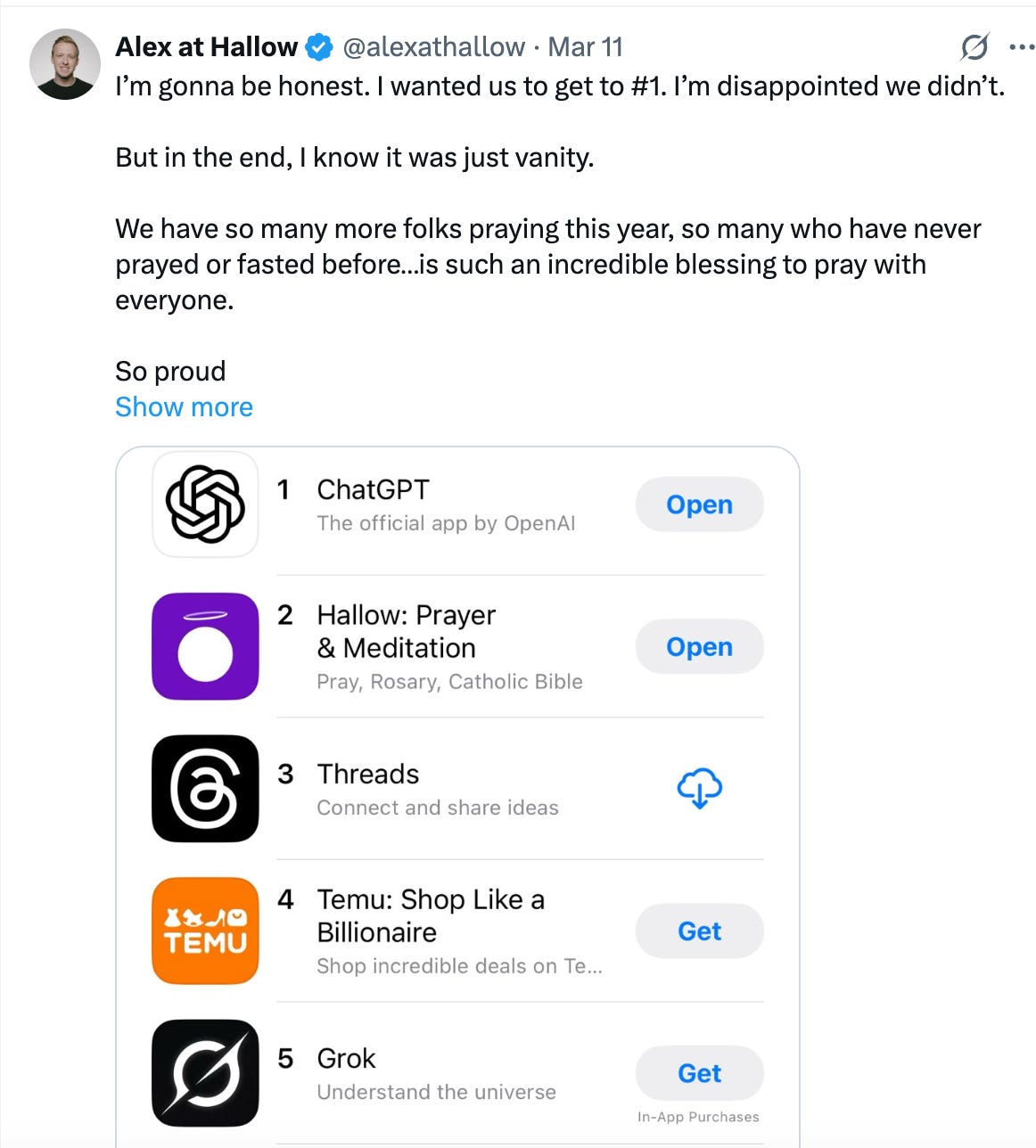

Hallow is a Christian prayer app launched in 2018 by a young American called Alex Jones, with over $100 million in investment from backers including Peter Thiel and JD Vance. It’s kind of ‘Headspace for Christians’ - a wellness app with traditional Christian faith and morality attached, featuring prayers from Christian celebrities like Gwen Stefani and Chris Pratt, and ways to link up to your local Catholic congregation. Its popularity soared last month, after it ran an advert during the Superbowl featuring Mark Wahlberg telling us to Stay Prayed Up. In March it was nearly the top-downloaded app on Apple, behind only ChatGPT.

As it soared to new heights of popularity this Lent, the Hallow app featured an unusual book choice for its Lent prayer challenge - The Way, by Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. Alex Jones told Aleteia, a Catholic news site, that The Way "has been one of the most impactful books to my own spiritual life and it is a blessing to get to share it with the community on Hallow’. In a video promoting the series, he said: ‘I keep it by my bedside every night.’ Thanks to Hallow’s promotion, the book went to number seven on Amazon.com’s non-fiction charts, as tens of thousands of Americans downloaded it.

Opus Dei is a controversial Catholic lay order most famous for featuring as the baddies in Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, but recently accused of cult-like practices and even human trafficking in a law case in Argentina. It’s also known for using other organisations and foundations to entice new recruits. Does Hallow or its founder Alex Jones have any links to Opus Dei? The secretive religious order does have powerful friends in the US, including Peter Thiel, Hallow’s seed funder, who was befriended by Opus’ chief US vicar Arne Panula when Thiel was a student at Stanford and who remained close for the next 40 years. But in this case, we don’t know - I emailed Hallow to ask but didn’t hear back.

Opus is having a moment in the US, thanks to its connections to White House insiders like Peter Thiel and Project 2025’s Kevin Roberts, as well as to the Christian Right philanthropy networks controlled by figures like Leonard Leo. But while Opus’ star is rising in the US, it’s in trouble elsewhere in the world. In Rome, the Pope is pushing for reforms; in Spain, control of Opus Dei’s largest shrine has been taken back by the local bishop; in Argentina, the organisation faces a court case for human trafficking - a case covered in a new series from HBO; and in the UK its reputation has been dented by critical exposes from the Financial Times and a new book by journalist Gareth Gore. Gore’s book, Opus, outlines what he describes as coercive, secretive and cult-like practices of control, not just of members but of companies and countries’ policies. Opus published a rebuttal that was itself many pages long.

This wave of criticism has been sufficiently strong to prompt Opus Dei to announce a process of ‘healing and reconciliation’, which apparently began five years ago but was announced by the prelate of Opus Dei, Fernando Ocariz, last year. I recently spoke to Jack Valero, head of the Opus Dei Information Office in the UK. He told me:

Some former assistant numeraries said, ‘we weren't very well treated’. And we thought, ‘Oh, that's a pity. We want to know more.’ It started as a labor dispute, but then it became much bigger. So we decided first of all, to listen to them, then to listen to anybody in the world who wanted to say something. So there's an email that you can write to and say, I want to be listened to about my gripes. And there is a mechanism where people of Opus Dei or not of Opus Dei can be listened to, and if there is anything to be done, we want to sort that out.

Ex-Opus members are not convinced - they point out that just providing a website for victims to contact Opus is hardly a deep process of self-reflection and change. ‘It’s a show for the Vatican’, says one former member.

This week, I want to dive into some of the concerns around Opus and how it says it’s responding, as well as exploring some of the intellectual currents in US Catholicism and politics at the moment. Here’s the agenda:

The founding vision of Opus Dei as a monastic order for the laity

Its cultic methods of recruitment (and how it says its changing)

Its cultic methods of programming / formation (and how it says its changing)

Whether it operates as a ‘secret society’ in business and politics

Pope Francis’ disagreements with Opus…and with JD Vance

1.A monastic order for the laity

Opus Dei was founded on October 2 1928 by Josemaria Escriva, the son of a textile manufacturer from Barbasto in the Spanish Pyrenees. When he was 26, Josemaria had what he took to be a divine revelation from God - a path to holiness involving the sanctification of everyday life and work. He envisioned a neo-monastic order, but not made up of monks retreating from the world, but rather a laity who worked in the world while committing to the same high standards of sanctity as a monk. The laity would be like a secret army for the re-Christianization of the world, totally obedient to the prelate of the order - him. It would recruit young, educated men and make them into ‘numeraries’ - who would rise to high office in politics and business, but live in Opus residences like monks. They would win influence, money and power for Opus.

Escriva’s spiritual director at this time was a Jesuit, and there are some similarities to the Jesuit Order - the emphasis on taking spiritual direction from a superior, the military-style hierarchy, and the tactic of cultivating and recruiting powerful people (see the comments section for a response from a Jesuit). But Opus was a lay order, not a clerical one. And where the Jesuits sometimes leaned leftwards, Opus’ politics have been perceived to be hard right (although the organisation denies it has any political agenda). Where the Jesuits had ties to liberation theology and social justice movements in Latin America, Opus Dei has had ties to right-wing military dictatorships or coups in Spain, Argentina, Honduras and Peru.

The Jesuits soon became alarmed by the rise of Opus. The head of the Jesuits, Fr Wlodimir Ledochowski, described Opus as ‘very dangerous for the Church in Spain’ and as having a secretive character’ with ‘signs of a covert inclination to dominate the world with a form of Christian masonry’. There may be something to that. In his best-selling prayer guide, The Way, Josemaria has a chapter on ‘tactics’, and (in my reading at least) he implies Opus should imitate the tactics of ‘evil secret societies’ but for good:

Don’t you see how evil secret societies work? They’ve never won over the masses. In their dens they form a number of demon-men who set to work agitating and stirring up the multitudes, making them go wild, so that they will follow them over the precipice and into hell. If you wish, you will spread God’s word, which is a thousand times blessed and can never fail.

Opus rose to prominence in Franco-era Spain. Franco, who ruled as a military dictator from 1939 to 1975, was a devout Catholic who slept with the severed hand of the mystic St Teresa of Avila next to his bed.

Francoism was different to Italian or German fascism in various ways - principally in its embrace of Catholicism (it was closer to the Catholic authoritarianism of Salazar’s Portugal or Vichy France). Escriva cultivated friendly relations with El Caudillo - ‘I ask God our Lord to bestow upon your Excellency every sort of felicity and impart abundant grace to carry out the grave mission entrusted to you’, Escriva wrote to Franco in the 1950s. The feeling was mutual. At one point more than 50% of the ministers in Franco’s government were members of Opus Dei.

Escriva’s The Way was published in 1939, and theologian Hans Balthasar suggested the influence of Francoism in the book’s emphasis on manly virtues, cultivation of will power, military discipline, and striving to be a strong leader or Caudillo:

You want to be an average person? To be lost in the masses? You were born to be a leader (caudillo)! There is no place for the lukewarm among us. Don’t let your life be sterile. Be useful. Make a mark. Will—energy!

Be strong and manly. In this way, you will first become the master of yourself and then the guide, the leader (caudillo) who commits himself to others, who drives them forward, who carries them away with your example, with your word, with your science, with your superiority (imperio).

Caudillo, steel your will so that God may make you a leader!

Opus gradually developed an international network of business and educational organisations - schools, university departments, charitable foundations, newspapers, record labels, even Banco Popular - Spain’s sixth-biggest bank - was controlled by Opus Dei, according to Gareth Gore’s new book. But these organisations were never directly owned by Opus or openly declared their affiliation. They were always owned or controlled by numeraries or ‘supernumeraries’ (similar to numeraries but they could get married and live outside of Opus residences) and it was never entirely clear how directly Opus controlled these organisations - Opus has always insisted there is no direct control.

Certainly, it seemed to bring in Opus a lot of money. It built up a portfolio of luxury real estate around the world. Here’s Opus’ headquarters in New York, on Lexington Avenue:

Here’s another of its properties in New York:

Here’s one of its mansions in Spain:

Here is its Villa Tevere in Rome, near the Vatican

These and other properties provided offices for Opus staff, residences for the numeraries to live in, and retreat centres for super-numeraries and the people Opus were looking to befriend and recruit. All of them were staffed by ‘associate numeraries’ - servants recruited from working class Catholic families, who were offered a path to holiness through domestic labour, often for little or no pay.

Today, Opus has an estimated 95,000 members in more than 60 countries around the world. Opus Dei offers lay people a hardcore neo-monastic path to sainthood, which didn’t require them to abandon the world of work. There’s something innovative in this, reminiscent of proto-Protestant medieval orders like the Brethren of the Common Life. And for many members and friends of Opus, no doubt, it has been a blessing and a spur to a saintlier life. But at the same time, a lot of people have now come forward to say they felt tricked by Opus Dei, trapped and enslaved by it, and they emerged feeling deeply damaged by their experience.

Jack Valero of Opus Dei UK tells me:

I think at the beginning it grew very quickly, and there was a lot of zeal. And when there is a lot of zeal for a good thing, maybe for somebody, this could be felt as pressure. Some left Opus and stayed on good terms, but others left and felt bitter. That’s very sad. We’re a religious organisation and don’t want to make anyone unhappy.

So let’s learn what errors Opus perhaps made and how it says it’s trying to reform itself.

Cultic recruitment

Right from the start, Josemaria’s strategy was to recruit members when they were young, through university residencies that weren’t advertised as being run by Opus Dei. He wrote a ‘secret manual for recruitment’ (in Gareth Gore’s phrase), called Instruction Concerning How to Proselytize, in which he commanded his followers to focus on recruiting young people as they were less set in their ways. His first Opus organisation was a university residency and Opus would subsequently set up schools, bookstores, foundations and business schools as nets to catch the fish of new recruits. ‘You must kill yourselves for proselytism’ Escriva said. ‘May God make your nets really effective!’

Gareth Gore writes:

Members were told to operate covertly, and to begin by planting seeds in the mind of the person being targeted. Drawing on his own methods, Escrivá even suggested that his followers might arrange charitable visits or cultural talks as a pretext for getting people together—but he warned against trying to recruit lots of people at once. “Never—ever!—try to capture a group,” he advised. “Vocations need to come one by one, unpicking—in this case—the group with snakelike calculation.”

Aggressive Christian evangelization is hardly confined to Opus Dei - Jesus told his followers to be fishers of men after all. But why not be open, rather than secretive, underhand and snakelike, in your recruitment methods? Opus also had a long-standing practice of trying to recruit teenagers as young as 14, especially if they were high-status. Gore quotes former Opus member Fr Vladimir Felzmann:

Members were encouraged to become pretend friends with the aristocracy of brains, blood, and wealth. Nowadays that is called grooming. Activities had a covert as well as an overt agenda. Camps, educational events were officially there to help young people. In fact, they were there to attract possible vocations.

The Financial Times’ Antonia Cundy found similar evidence of Opus recruitment focused on teenagers, sometimes as young as 14, in an article published last year. Cundy interviewed several ex-members, one of whom says:

At a get-together about this boys’ football club that they ran . . . they started going through the names of the individual boys and how predisposed they might be to join. “It was: ‘Is this person close to the activities of The Work? Is that a person you could see ‘whistling’ in a year or two?’ It was that explicit.

You can read a similar account by a former numerary here, who taught a computer class for foreign students in the US, organized by Opus Dei:

About a week after the girls arrived, I was told to attend a meeting with all of the numerary members involved with the program…One of the numeraries had a sheet of paper typed up with the names of the girls attending the program. As each name was called, different numeraries would relate how close the girl was to joining Opus Dei, often making statements such as "she went to confession" (with an Opus Dei priest); "she's been going to daily mass"; "her sister is in Opus Dei," etc. Then a plan would be devised, written down and a numerary would be chosen to carry it out.

Opus used a similar tactic with ‘intellectuals’, as Opus refers to young leaders in culture, business or politics - they are courted, flattered, and slowly brought over to the Opus fold. A similar tactic is used today in the US by new Christian Right networks like Teneo Network, which seek to ‘recruit, connect and deploy the most talented Conservatives’ in order to ‘crush liberal dominance’. Teneo’s members include Peter Thiel, Leonard Leo (a powerful Catholic philanthropic fixer with ties to Opus Dei) and vice-president JD Vance.

Father John McCloskey was the Opus vicar responsible for recruiting DC insiders to Opus in the 1990s. He told the New York Times: ‘There is a certain gift that Opus Dei has in terms of dealing with people of influence.’ His converts included Newt Gingrich, Senator Sam Brownback, and Trump’s former director of National Economic Council Larry Kudlow.

The targets for conversion would be ‘love-bombed’ - showered with friendship and compliments by Opus members close to their own age. They would be wooed with something like this: ‘You have a vocation. Secular culture is a barren demon-infested desert, you’re too smart to be fooled by it. Christianity (i.e Catholicism) is the only saviour for western civilization. God is calling you to great things on Earth and you will be fast-tracked to heaven after death, and perhaps even sainthood.’ Targets would be worked on for months, and then invited to an Opus retreat where the pressure would build to a dramatic emotional climax - the conversion and pledge to Opus. But some ex-members say they had no idea what they were signing up for. ‘Opus Dei does not reveal all of the lifestyle changes numeraries make before they join’, says one ex-numerary.

Cultic re-progamming

Escriva would bring new recruits into Opus in a ceremony named ‘the Enslavement’. He asked them ‘Will you put your whole life at the service of God in his Work?’, then gave them a ring with the date of the ceremony and the word Serviam - I serve.

After that, the numerary or assistant numerary would move into an Opus residency, and their whole life would come under Opus control, just as if they had joined a monastery. Every minute of the day was accounted for, from the moment they rose from their bed (a hard board if they were a female numerary) and knelt on the floor to pray. Opus had rules for what numeraries or assistant numeraries wore, what they listened to, watched or read; any received letter was read by a superior, any letter sent out was edited; any phone call was made in the presence of others; and any access to others was strictly controlled - you might see your family once a year. You were even separated from the person who recruited you, who you thought was your special friend, because close personal friendships were frowned on.

Opus members are expected to mortify their flesh. ‘Treat your body with charity’ Escriva writes in The Way, ‘but only as much charity as you’d give a treacherous enemy’. Members should practice fasting: ‘Among the ingredients of your meal include that most delicious one, mortification’, writes Escriva. Members are expected to wear a cilice - a spiked metal chain - around their thigh, and also to whip themselves with a small whip called the disciplines, every day. Escriva, like a true Spanish Catholic, was very keen on such practices, and would apparently whip himself until the blood splattered on the walls. He writes in The Way: ‘Blessed be pain. Loved be pain. Sanctified be pain…Glorified be pain.’

The aim of these methods is a state of total devotion, submission and obedience to God and to Opus Dei’s military-like hierarchy. There was a cult of personality around Escriva while he was alive, and even more now he’s been canonized. One associate numerary remembers (in the HBO series The Heroic Minute), ‘I would sometimes wonder, are we following Jesus or Josemaria Escriva?’ Gore interviews another former member: ‘Whatever the director told me to do was God’s will. Opus Dei and God gradually merged into one.’

One of the key practices at Opus is regular consultations with a spiritual director. Escriva writes:

You wouldn’t think of building a good house to live in here on Earth without an architect. How can you ever hope, without a director, to build a castle of sanctification to live forever in heaven? …You need a director who knows what God wants…your own spirit is a bad advisor, a poor pilot to steer your soul…That’s why it is the will of God that the command of a ship be entrusted to a master…

The emphasis is on doubting your own conscience and submitting entirely to your spiritual director. You should open up completely - ‘don’t hide those suggestions of the devil from your director’, Escriva writes. There’s a similar practice of spiritual direction in the Jesuits, except that, in Opus, according to multiple reports, the details’ of members’ intimate conversations with their directors would be recorded, shared with Opus leadership, and kept on file as ‘report cards’. Gareth Gore writes:

These report cards would eventually evolve into the internal “reports of conscience” that local directors would prepare for the regional headquarters, using information gleaned from members during the supposedly confidential spiritual guidance sessions—a mainstay of Opus Dei’s control over its members’ lives that would remain for decades to come.

Gore told one interviewer:

Opus Dei has more in common with the KGB or the Stasi than it does with other parts of the Catholic Church. It has this meticulous recordkeeping. I spoke to one prominent D.C. conservative who said he had incontrovertible evidence that [Opus’ chief vicar in the US] had collected deeply personal and compromising information about him during Confession and then passed it on to senior members of Opus Dei.

This, I believe, is against Catholic canon law, and Pope Francis recently insisted Opus stop it. So too is the practice, asserted by ex-Opus members but fervently denied by Opus itself, of insisting that Opus members only confess to Opus priests, and that other priests ‘lack grace’ . Here’s one ex-numerary, currently bringing a lawsuit against Opus, talking about this:

Members were apparently sometimes told that if they leave Opus without permission, they will go to hell. To leave without going to hell, they need the permission of the prelate, the head of the entire organisation, and this was sometimes very slow to come. One ex-numerary who left after her family pleaded with her to return to them recalls:

After a couple of days, the director called me and asked when I would be returning. I said that I was not. She tried to convince me to return to the center, by saying "Opus Dei is your real family." For four months after I left, I was harassed by members of Opus Dei. Maria actually came to my place of work. When I told her I was busy and on my way to a business meeting, she followed me on the subway, all the while talking at me about how if I did not come back, I would go to hell.

Members who were wavering or upset or having a breakdown were sometimes referred to Opus doctors and psychiatrists, who would prescribe Rohypnol or anti-psychotics or other medication. Really problematic members, perhaps those who knew potentially dangerous secrets of the organisation, were even placed in asylums.

This sounds like totalitarian control of members’ behaviour, thoughts and emotions - classic cult behaviour. But maybe this is to take a modern, liberal perspective on the rigours of the monastic life. I guess a monastic order does seek total control of a person’s inner and outer life…It seeks to be an intense crucible for spiritual formation, a forge for saints. And sometimes, writing about culty organisations, one should keep in mind - some people are up for this level of spiritual commitment and obedience to an order. Some people want this level of spiritual direction in their life, and flourish under such high-control regimes. This is an important point to keep in mind.

The key issue with spiritual or religious communities is this: are adults (or teenagers) joining of their own free consent, fully informed of what they are signing up for? Or is an organisation using non-transparent, deceitful, high-pressure coercive methods to get people to join and to keep them under the organisation’s control? Is the organisation alive to the possibility of spiritual harm and abuse, or is it careless, deaf to complaints, and overly-convinced of its own rectitude?

It reminds me of debates around New Age gurus - some people are genuinely up for intense, alternative, somewhat extreme lifestyles and practices involving submission to the will of another. But you need to check in very carefully, repeatedly, that they are consciously consenting, or the risk of harm and abuse is very high. And if many people are leaving your organisation and saying ‘this was not safe, or honest, or ethical, and I feel harmed’, you have a big problem. You cannot trust that ‘we’re on the side of God’, everybody thinks that. We are fallen human beings capable of committing harm - all of us, New Age guru or Catholic saint.

Opus’ Jack Valero tells me:

We’re no longer allowed to recruit teenagers…And we ask much more now [before people join]: do you know what you’re doing? Do you really want to do it? We extended the ‘formation’ phase [before joining] to several years. And if somebody wants to leave, we make sure that we understand why and we accept it, and also, [see] if there's anything they need and we can help them. [As for people saying that apostates would go to hell] I was very upset that anybody had said that to someone else. I think is very counterproductive. [Re the practice of spiritual directors sharing confidential information from confession with Opus Dei] That is now forbidden.

4) Opus Dei as a secret society in business and politics?

The longest-standing criticism of Opus, going back to the 1930s, is that it is a secret society acting in its own hidden interests, pulling strings behind the scenes in companies or even entire societies - that even though it was inspired partly by Escriva’s animus against freemasons, it is itself this sort of ‘Catholic masonry’ or ‘Catholic mafia’ which governments should watch out for.

After the paywall, does Opus have a political agenda, the rise of post-liberalism and Integralism in US Catholic intellectual circles, and Pope Francis’ tussle with Opus…and with vice-president Vance.